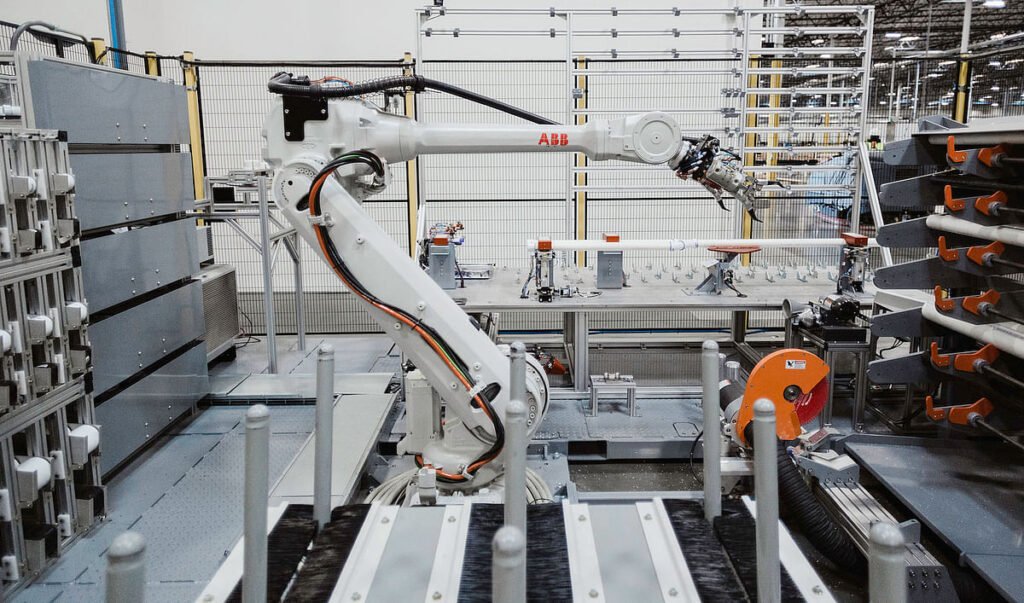

Inside the Katerra manufacturing plant before it closes in 2021. Image courtesy of Katerra

Despite a general consensus that the United States needs more affordable housing, startups focused on affordable housing and more efficient construction technologies received less funding in 2024 than in recent years. Meanwhile, a series of high-profile bankruptcies, closures, and struggles have been reported among startups working on this issue. Why did this happen?

It’s a tough time for housing startups. Late last year, unicorn home manufacturer Veev collapsed and was reportedly sold for $100 million despite once being valued at $1 billion. A few months ago, Business Insider covered the issues of Nevada-based tiny home startup Boxabl, highlighting what it called “production issues, questionable governance, and lavish founder spending.” Meanwhile, in 2021, Archinect reported that ambitious construction startup Katerra had collapsed after years of struggles and bailouts.

“Overall, funding for startups focused on affordable housing and more efficient construction technologies is significantly down compared to a few years ago,” Crunchbase wrote late last year, adding: “While funding rounds are happening, no one would say affordable housing is a hot topic for startup investment. There are barely any new unicorns to be seen, and no buzzworthy companies expected to go public anytime soon.”

Looking at the current housing demand across the United States, the idea that affordable housing isn’t a “hot topic for startup investment” seems absurd. In 2021, Archinect reported that the U.S. needs an additional 5.5 million homes to make up for a decades-long slowdown in homebuilding. CNN reports that the figure will be 6.5 million by 2023, and in recent weeks, NPR reported that the shortfall is “between 4 million and 7 million.”

It would be an exaggeration to say that the design and construction industry is being disrupted by startups to the same extent as other sectors of the economy.

In an economy where startup activity is sluggish, entrepreneurs, angel investors, and venture capitalists would be forgiven for not treating the housing issue as a priority. But it’s fair to say the United States is experiencing a golden age of startups. According to The Economist’s analysis of Census Bureau data, new business applications in the United States (a measure of startup activity) have already increased over the past decade, from about 200,000 per month in 2010 to 300,000 per month in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of new technologies such as generative AI have pushed this monthly average up 80% from pre-pandemic, with 5.5 million new business applications filed last year. “Everyone’s a founder,” The Economist declared in releasing the numbers.

This isn’t to say that the affordable housing issue is being completely ignored by the startup ecosystem, or that all housing startups are struggling. Over the past year, Archinect’s Job Highlights series has highlighted job openings at two startups exploring new solutions to affordable housing. The first, Assembly OSM, is a venture-backed startup born out of SHoP that aims to disrupt high-rise construction. The other, Cover, is developing a home design and manufacturing system inspired by the automotive industry, its founders explained in a 2021 interview.

Elsewhere, our editorials recently covered the progress of San Francisco-based Cosmic, which has raised $1.5 million in funding for its microhome product designs and whose first products are for sale in California; meanwhile, Airbnb co-founder Joe Gebbia’s ADU company Samara has begun production of units at a new factory in Mexico, as we reported in March. In addition to activity in the prefab and ADU markets, the 3D printed building field continues to make strides, whether through ICON’s suite of new technologies and products recently announced at SXSW, or the many material innovations aimed at reducing housing production costs that we reported on in our editorials this year.

Despite all this activity, it would be a stretch to say that startups have disrupted the design and construction industry to the same extent as other sectors of the economy. No company, or group of companies, has done for homebuilding what Airbnb did for short-term accommodation, what Uber did for transportation, what Tesla did for electric cars, what Facebook did for social networking, or what OpenAI is now doing for artificial intelligence.

Why is the topic of affordable housing not garnering much interest from investors? Why has there been a recent spate of high-profile failures and struggles among the relatively few startups tackling the challenge?

“Katera was a company started by guys from Silicon Valley who wanted to show the construction industry how outdated they were,” Marc Elrich told Business Insider in January. How we build: Restoring dignity to construction workHe believes the failure of housing startups like Katerra stems from leadership and investors coming from outside the construction industry, and that a combination of overly ambitious plans, little expertise and “arrogance” led to their downfall.

A month later, Roger Valdez, director of the Center for Housing Economics, wrote in Forbes that unlike the technology industry, housing is “highly dependent on public opinion, not just consumer needs, and is therefore unstable.” Valdez also blamed land use and housing policy for the difficulty of housing innovation, noting that “a regulatory mess at the state and local level makes it impossible.” Elrich also criticized regulations in a conversation with Business Insider, arguing that “restrictive policies” on housing and land use are based on a long-held perception by officials that factory-built housing is inferior to traditional housing.

For fixed, long-term products like housing, where innovation and delivery can be measured in years rather than weeks or months, the rapid fluctuations in the dollar value of such products are not suited to a VC culture that demands fast, dynamic, and adaptable solutions.

Then there’s the complicated issue of demand. Elrich argues that one of the most significant obstacles to investing in modular housing is the perception that demand for modular buildings is uneven. The article states that investors “are not convinced there is sufficient and consistent demand for modular housing in most markets” outside of markets with large amounts of repeating components, such as hotels, dormitories, or apartment complexes with identical units. “If you have to adjust the design details, at that point it becomes cost-prohibitive and much more advantageous to build on site,” Elrich noted.

Beyond prefabricated and modular homes, the demand issue is similarly complex for the housing market as a whole. While there is a general consensus that the United States needs more housing in the long term, the housing market is cyclical in the short to medium term, with property values rising and falling depending on interest rates, economic conditions, the desirability of certain areas, and myriad other factors. For a fixed, long-term product like housing, where innovation and delivery can be measured in years rather than weeks or months, rapid fluctuations in the dollar value of such a product do not lend themselves well to a venture capital culture that demands fast, dynamic, and adaptable solutions.

This cyclical market condition contributed to WeWork’s demise. Despite targeting office space rather than residential, WeWork fell victim to cyclical fluctuations in real estate values. WeWork’s business model, which involved signing long-term leases for workplace buildings that it could sublease to individuals and companies, depended on the rental value of such space rising, or at least remaining stable. That did not happen. Founded in 2010 and once valued at $47 billion, WeWork was on the brink of collapse when the scale of the company’s losses became clear in a messy IPO in 2019. In November 2023, WeWork filed for bankruptcy after demand for office space plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

WeWork is not a technology company, nor did it offer any specific innovations in how physical space is designed, delivered, or used.

Of course, that’s not all: WeWork’s failure is often blamed on the eccentric personality and poor decisions of its founder, Adam Neumann, who was ousted from the company in 2019. Neumann also announced that he would be founding a new residential-focused startup called Flow in 2022.

But Neumann’s first mistake may have been to brand WeWork as a tech startup. Born out of the Silicon Valley boom, where digital platforms were redefining the user experience of physical products—from phones to cars to hotel rooms—WeWork, its founders, and its investors viewed real estate in the same light. But aside from its TED-style keynotes and slick apps, WeWork was essentially a commercial leasing agency. It wasn’t a tech company, and it offered no tangible innovation in how physical space was designed, delivered, or used.

Thus, a lesson from WeWork’s collapse may be to recognize that innovation in housing is different from the tech startups it tried to emulate. Whereas in tech, world-changing innovations can come from a laptop in a dorm room, innovation in AEC requires much more upfront investment before a solution becomes evident: materials science, factory construction, structural testing, and more. Whereas tech solutions can pivot instantly in response to changing market conditions, innovation in housing is inherently less agile. Whereas tech startup founders can bootstrap and build proofs of concept before approaching investors, housing innovators lack that personal capital, and architect and builder clients are understandably resistant to real projects being used as experiments.

“There’s no General Motors. There’s no Tesla. There’s no company that’s willing to spend 10 years before making a lot of money,” Elrich told Business Insider. Innovation in affordable housing design and delivery — one of the most pressing challenges facing the US and the world — must navigate a complex regulatory environment, an unpredictable and cyclical economic environment, and a venture capitalist environment designed primarily to make a quick buck, not solve real problems.