Colorectal cancer is currently the leading cause of cancer death among young men and the second leading cause of cancer death among young women.

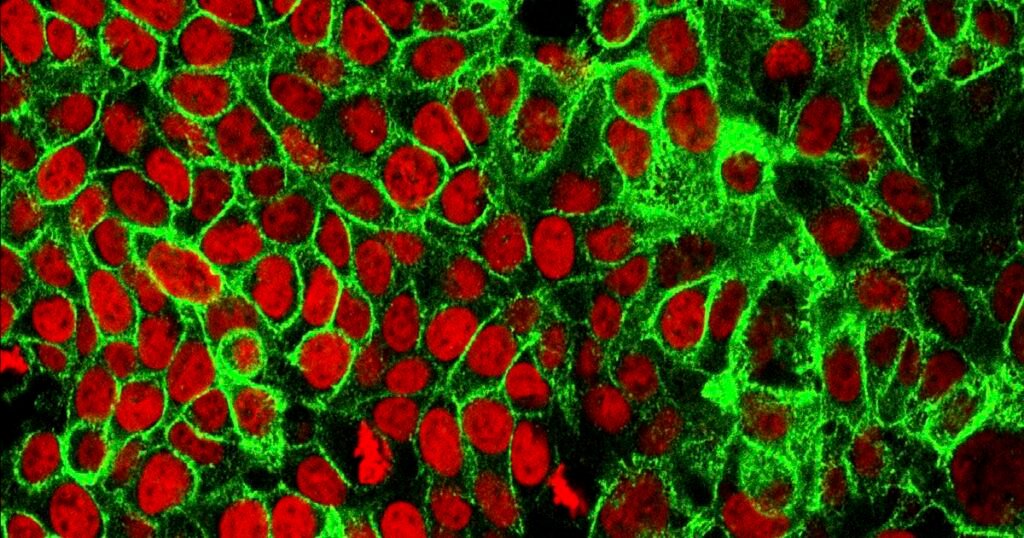

(NCI Center for Cancer Research | The Associated Press) This microscopic image made available by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Research Center in 2015 shows human colon cancer cells with red-stained nuclei. On Friday, May 29, 2020, doctors reported the success of a new drug that can better control certain types of cancer, reduce the risk of recurrence, and make treatment simpler and more affordable.

One Friday movie night in the summer of 2020, my phone rang.

I was watching Black Panther with my son when one of my friends called and asked if I had heard the news about actor Chadwick Boseman. Feeling a hunch, I asked him what he meant.

After a pregnant pause, he replied: “Mark, he’s dead.”

And the reason my friend called me, a gastrointestinal oncologist, was because the cause of death was colon cancer.

I paused the movie and stared in disbelief at the screen where Chadwick Boseman was literally frozen in place playing a superhero.

Even with new clinical eyes, I could only recognize him as a healthy actor in his prime. It’s hard to imagine him having anything other than perfect health.

Still, there was a part of me that understood this cognitive dissonance. Because in my professional life, I have cared for more and more young patients with the same type of cancer.

This troubling increase in case numbers is sometimes described as the “birth cohort effect.” This means that a patient born in 1990 has twice the risk of colon cancer (and four times the risk of rectal cancer) compared to a patient born in 1950 faced at the same age! ). Year.

Colorectal cancer is currently the leading cause of cancer death among young men and the second leading cause of cancer death among young women (defined as those under 49 years of age).

There is a common misconception that cancer is simply a result of aging. While it is true that cellular aging is the cause of aging, cancer is almost exactly the opposite, and is perhaps the closest thing to immortality on a microscopic scale: cells that can divide indefinitely.

In fact, the absence of growth inhibition is itself a hallmark of cancer.

So, why is this happening? In his book “Genes,” author Siddhartha Mukherjee explains the cause of all diseases, including cancer, using the formula: genetics + environment + triggers + chance. I proposed that it be summarized by.

Looking at the components of that formula, up to a quarter of early-onset cases are caused by syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis, which can be transmitted from generation to generation. It is estimated that it may be due to genetic risk. Colorectal cancer (commonly known as Lynch syndrome).

But still, most cases should be explained by other causes and we often call them “sporadic” because they occur in the absence of a pathogenic family history.

One way to think about this acquired risk is the “exposome.” Colorectal cancer aims to measure the biological effects of everything that passes through your intestines during your lifetime, from food to antibiotics.

Nutritional epidemiology (the influence of diet on disease at a population-wide level) is notoriously difficult to study, but some researchers have found that cooking red meat at high temperatures can lead to the release of heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatics. It has been suggested that carcinogens such as group hydrocarbons may be produced.

A study within the UK National Health Service found that patients with young-onset colorectal cancer were more likely to have been prescribed antibiotics in childhood, perhaps subsequently changing the bacteria in their gut flora to favor carcinogenic species. This suggests that there is a high possibility that the change has occurred in the same direction.

Partly in response to this demographic shift, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (the government agency most responsible for issuing screening recommendations) will increase the number of initial screenings for colorectal cancer for average-risk individuals in 2021. The age was lowered from 50 to 45.

While home fecal testing is becoming increasingly popular, the gold standard for screening is likely to remain a colonoscopy. That’s because during the procedure, the doctor (usually a gastroenterologist or surgeon) can not only identify the precancerous polyp, but also remove it and block off the so-called adenoma. -Sequence to carcinoma. In other words, polyps that are completely removed during a colonoscopy no longer have the potential to invade and grow into true cancer.

However, even this early screening may not be enough to “catch” colorectal cancer in some patients.

Slightly more than 70% of young-onset cases are stage III (locally advanced) or stage IV (metastatic) at the time of diagnosis, and therefore often require chemotherapy.

Just this spring, Melissa Inouye, a religious scholar and historian for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, passed away at the age of 44 from metastatic colon cancer. She was first diagnosed at age 37. She was mentioned in her book that she was otherwise in great shape, ran marathons, and ate organic produce grown in her home garden.

Tragic cases like those of Chadwick Boseman and Melissa Inouye have been linked to gastrointestinal problems in young patients, especially bleeding, but also changes in toilet habits such as thinner stools, pain during defecation, and unintentional weight loss. This is a call to action to take more seriously the following:

Screening is not the same as diagnosis, and patients with symptoms deserve to see a doctor at any age.

(Photo courtesy of Intermountain Health) Mark Lewis

mark lewismedical doctor, Director of Gastrointestinal Oncology at Intermountain Health.

The Salt Lake Tribune is committed to creating a space for Utahns to share ideas, perspectives and solutions to move our state forward. To do this, we need your insight.Find a way to share your opinion herePlease contact us by email below. voice@sltrib.com.