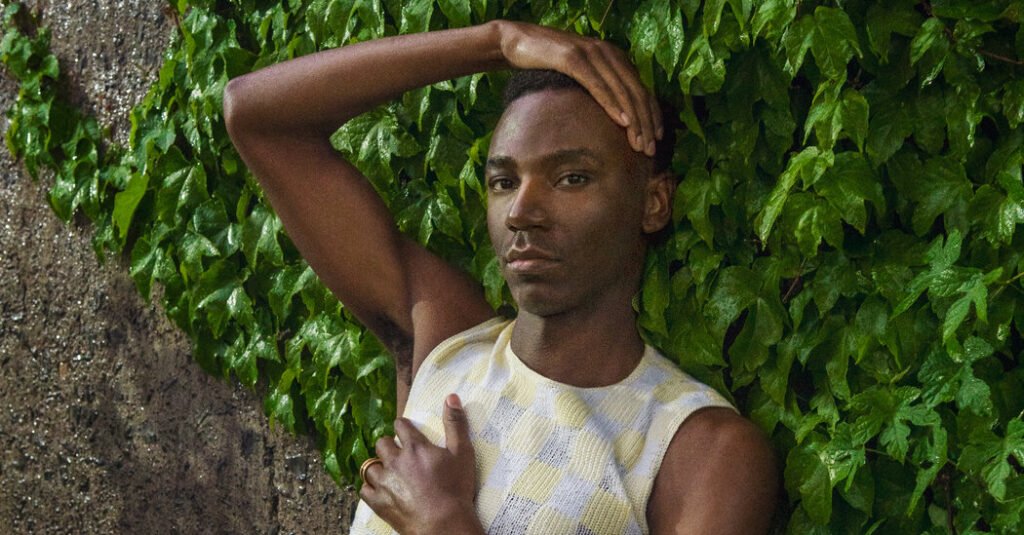

Comedian Jerrod Carmichael holds his head in his hands like Henri Vidal’s 19th-century Cain statue after killing his brother Abel on HBO’s new series “The Jerrod Carmichael Reality Show.” It takes a surprising amount of time.

The series focuses on Carmichael’s agonizing process of coming out, bravely taking that step and coming to the realization that, in a sense, the old self must die in order for the new self to live. That may be appropriate since, like many people, Carmichael’s focus is on the process of coming out. To put it more pointedly, you must kill the false you.

Even now, coming out is not always followed by celebration and celebration. And like Carmichael, and like me, people who come from religious families and struggle to reconcile their religious beliefs with our claims to be free and noticed. It can also be distressing for people who have family members who are pregnant.

Revealing that dilemma to the world is one of the great services Carmichael performs in his series.

But of course, this show isn’t actually “reality.” That can’t happen. Carmichael says he’s trying to “do the Truman Show” himself, but it’s nearly impossible. The cameras aren’t live streaming his life. They collect edited and curated footage of the moments we see.

The series tries to address this point in the first episode, when Carmichael’s anonymous friend (who wears a mask on screen) says “this isn’t true” about the presence of the cameras, and Carmichael He said what he was doing was “making masturbation public.” ”

Certainly, there is truth to that observation. Carmichael seems to find something exquisite in his anguish, not only his own discomfort but also that of his audience. His specialty is using awkwardness to make the audience squirm in pregnant silence. Remember his smart, insightful, yet somehow jarring monologue at last year’s Golden Globes?

He is passionate about the idea that he can tickle the belly of any trauma and that even nervous laughter is laughter.

This style of comedy brought him success and praise. In 2022, he won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Writing for his HBO stand-up special Rosaniel, in which he came out as gay.

The new series explores his life as a newly come out gay man, but it’s in the exploration of his humanity that Carmichael’s project truly shines. As the ancient playwright Terence wrote, “I am a human being; nothing human is foreign to me.” This is proof that the human condition is universal.

Most of all, Carmichael is not driven by love interests (he confesses his feelings to his friend, hip-hop artist and producer Tyler, the Creator, only to have them dismissed) and is unfaithful. I have problems with human relationships, such as: A bad friend to his partner and desperate to be accepted by his parents.

The show also depicts how difficult it is to achieve emotional maturity, and how it requires the emotional vulnerability and courage that many people struggle with to achieve moral responsibility. As Carmichael says, “It’s easier to say ‘I’m gay’ than ‘I’m sorry.'”

But perhaps one of the most heart-wrenching and important themes in the series is the incongruity and direction of a character who comes out late in life and brazenly centers sex in his gay identity and journey. It deals with emotions that have become numb.

“I came out late in life, basically when I was about 30,” he said, adding sarcastically, “In gay era terms, I’m 17.” He says that’s one of the reasons he always wants to have sex. But he struggles with his voracious sexual desires, trying to understand whether they are a sign of liberation or disorder.

In a conversation with a therapist, he said he was a “very sexual” child “with older children” and had at least 1,000 sexual partners.

He cheats on her boyfriend multiple times and eventually the two agree to an open relationship, but this comes with risks. Rather than being purely obscene, this is an honest expression of the complicated relationship many people have with sex, sometimes used to distract from pain or injury.

As Carmichael says, he uses sex to escape.

And he continues to try to heal his uneasy relationship with his parents. Both of his parents are the cause of his suffering. His father was unfaithful to his mother and avoided him when he was young. His mother did not extend her unconditional love to him after he came out. But Carmichael doesn’t look like a saint in this production. Although he desperately seeks and expects grace from his parents, he seems unable to grant it due to his parents’ shortcomings. If Carmichael is the hero of this series, he’s his X-Men type: complex and overcoming trauma.

But as this series makes clear, the love between parent and child can be irresistible. Like a twig emerging from the ashes of a forest fire, even after the worst has happened, it can reassert itself.

Carmichael’s show joins an important body of work that looks at life through a queer lens, particularly a somewhat unconventional black gay lens, but it’s not just aimed at gay audiences. It is ultimately about universal themes of hurt and healing, the search for personal freedom, and what it means to love and be loved.