The RSF has been besieging El Fashhar for over a month, and its population has been rapidly increasing with refugees from cities and towns across Darfur fleeing the 13-month civil war. Due to the widespread violence, many of El Fashhar’s permanent residents are now seeking refuge in crowded camps in the area.

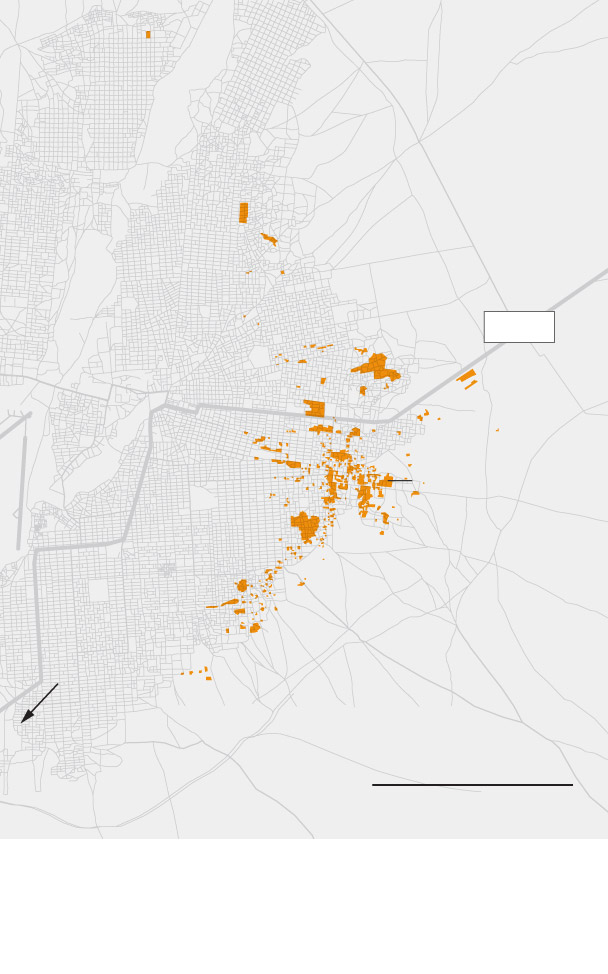

Structures destroyed since March 21

Zamzam Camp

Approximately 6 miles south

Source: Yale School of Public Health

Humanitarian Research Lab (Damage Analysis)

Open Street Map

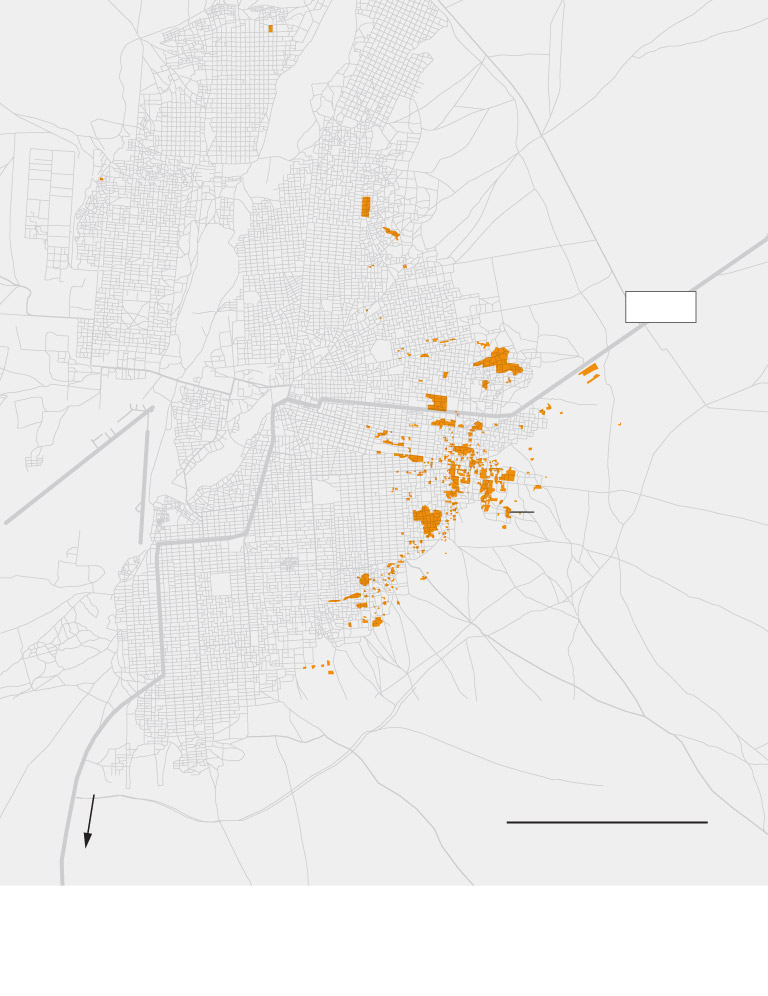

Structures destroyed since March 21

Zamzam Camp

Approximately 6 miles south

Source: Yale School of Public Health, Humanitarian Studies

Lab (Damage Analysis); OpenStreetMap

Conflict-related damage or destruction since March 21

Zamzam Camp

Approximately 6 miles south

Sources: Yale School of Public Health Humanitarian Lab (Damage Analysis); OpenStreetMap

Although the siege of El Fasher only began in earnest recently, the situation has been desperate for some time. In February, international monitors estimated that a child was dying every two hours in the Zamzam IDP camp on the outskirts of El Fasher. Now, with no aid arriving, severe famine seems imminent.

The fall of El Fasher gives the RSF near-complete control over western Sudan and a significant advantage in the fight for control of the country, making a return to genocidal violence in Darfur more likely.

The RSF’s leadership includes many former Janjaweed fighters who, when allied with the government in the 2000s, attempted a scorched earth campaign to flush non-Arab ethnic groups out of western Sudan.

At the time, an ad hoc coalition of journalists, academics, students and prominent activists was formed to put pressure on Sudan, its international sponsors, and the multinational corporations that do business with them.

Although the persecution of non-Arabs in Darfur never fully ceased, the coalition achieved some modest success. In 2004, the African Union sent a peacekeeping force, which was later “reconstituted” as a UN force with the approval of the Security Council. In 2005, the Security Council referred the case to the International Criminal Court, which later issued arrest warrants for Janjaweed leaders and Sudanese government officials who aided and abetted the massacres, including Head of State Omar al-Bashir. In 2006, President George W. Bush, who publicly used the word “genocide” to describe the situation, signed a bill imposing sanctions on the Janjaweed. and the Bashir government.

Until last year, a fragile peace existed that seemed to protect Darfur’s non-Arab population from genocidal persecution.

But today, the Janjaweed seem likely to succeed. The fall of El Fasher could give them the opportunity to complete their genocidal plans. A Human Rights Watch report last month described in gruesome detail how the RSF launched a campaign of torture, rape, assassinations and massacres against civilians when it seized the city of El Geneina last year. In October, a BBC reporter reached a similar conclusion about the RSF’s takeover of Nyala. El Fasher is the last refuge for many of Darfur’s non-Arab civilians. Its fall would likely mean brutal treatment for resisting conquest for more than two decades.

Since seizing control of the roads around El Fasher in April, RSF forces have been treading cautiously. Whether that’s because the resistance has been stronger than expected or because the hold is simply too tight, it’s unclear, but RSF forces can afford to wait. With RSF weapons and reinforcements arriving, their besieged enemy has nowhere to run.

RSF has so far calculated correctly that it can afford to wait, since there has been little response from the world. This is a tragedy in itself. It represents an abdication of the international community’s responsibility to protect those under threat.

The world urgently needs to respond, but the options are narrowing by the day. The best option at this point is to negotiate a ceasefire and get aid into the city. However, only the United Arab Emirates, known as the RSF’s main international sponsor, seems capable of exerting the necessary pressure to stop the fighting. Unfortunately, an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council on May 24th did not produce any concrete progress on an agreement.

The only other option would be to deploy a UN-authorized peacekeeping mission to protect civilians, a mission the US and European countries would be ready to provide, but which might force the UN to defer to the African Union to raise and organize the forces.

The mission of this operation is, first, to prevent direct attacks on the civilian population of El Fasher and its refugee camps, and, second, to secure El Fasher’s airport for the delivery of humanitarian supplies.

A more durable resolution to the crisis will require the Sudanese people to reach a lasting political compromise. That will likely be a compromise between the military elites fighting each other in the fighting, the Khartoum-based civil society groups representing the democratically elected government that was ousted in 2021, and local ethnic leaders. It will probably involve power-sharing, at least initially, but more fundamentally, the recognition of the civil and human rights of all Sudanese people. It will also require a strategy to pursue accountability for the horrific crimes that are perpetuated in this conflict. But this can only be achieved once the RSF’s genocidal intent is thwarted.

Sending in an international peacekeeping force would be the most extreme measure to prevent atrocities. It would not be easy to put together, given all the other crises currently rocking the world. But after so long of global indecision, Sudan is facing a return of genocide with no other option to prevent it.