As I slowly flipped through Wednesday morning’s New York Times, my first cup of black coffee didn’t quite do its job. But page B11 certainly did.

There, my childhood filled the entire page. Two large headings spanned the top and center of her B11 page, evoking a rush of very special, but very different, memories. One memory was pure fun. The other is powerful and meaningful to the true formation of America.

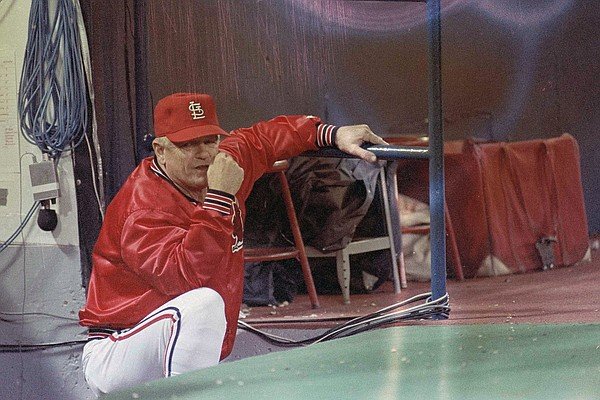

The headline said that Whitey Herzog and Carl Erskine, two famous baseball stars of the mid-’90s, had just passed away. Just reading their names brought back memories of fleeting but eternal moments with two teammates who were not just sports stars, but cultural constellations. Now we’re talking about Satchel Page and Jackie Robinson. They were emblematic of a time when America was finally, belatedly beginning to make changes in racial justice and civil rights.

Whitey, Satchel, and Me: As I read Herzog’s account, my mind began to relive the moment in 1957 when I was one of the kids waiting for autographs after a night game at the old minor league Miami Stadium. Ta. Page, a famous aging pitcher in the baseball world with an ageless arm, was still active. He never retired and became a star player for Bill Veeck’s new AAA minor league team, the Miami Marlins.

Paige was always the last to leave. And they had turned off the stadium lights before Page finally showed up with a young Herzog in tow.

“There are no signs tonight. It’s too dark to see,” Page said. So all the children left. Except for one thing. I looked up at this tall, slim historical icon with my red-bound signed book in hand and decided to get it.

“Oh, I can imagine how hard it is to see with my old eyes tonight, Mr. Page,” I said. “But my young eyes can still see clearly.”

Herzog burst out laughing and convulsing. Paige almost did the same, but she pulled herself together and started doing a little vaudeville comedy. “Old eyes? I still have young eyes! I’ll show you. Give me that book!”

With a hiss, the old star signed “Satchel Paige.” The legend returned my book, glistening with his victory in the major leagues. End of story.

Jackie and Me: Erskine’s biography talked about his friendship with Robinson. And it was a mental re-enactment of my most special moments with my childhood (and adult) heroes. It actually happened when I was Newsday’s Washington correspondent. When I arrived early for a New York City interview with Governor Nelson Rockefeller, one of his guests came out into the lobby. He was a large, gray-haired black man who walked like an old man. I introduced myself to Jackie Robinson, trying not to look like the world’s oldest kid asking for an autograph. My idol grabbed me by the arm and took me outside and asked if he could help me across the crowded Central Park West to his car and driver.

Diabetes left him lame and his eyesight impaired. After his car drove away, I gathered myself and interviewed the New York Governor. Robinson died in 1972 at the age of 53.

The best tribute to Robinson I’ve ever seen was written by his Dodgers teammate and friend Erskine in his book, “What I Learned from Jackie Robinson.” The Erskines’ fourth child, Jimmy, was born with Down syndrome. He won medals in the Special Olympics and had a career in restaurants, but died last November at the age of 63.

“I often felt like Jackie came into my life and taught me how to direct my energy and anger toward what was happening around me, about society’s lack of acceptance of Jimmy and Down syndrome and other birth defects.” Erskine wrote. “…Jackie held the Rookie of the Year and Hall of Fame plaques, and my Jimmy went on to win gold medal after gold medal at the Special Olympics. I wish Jackie had lived to see those days. Jackie had a lot of things she wanted to do.” Same with Jim’s success. ”

Amid all the noise and well-manufactured outrage that makes the news today, let us remind each other that what has always made America great is our shared entertainment values, never politics. It is useful for.