Exchange-traded fund providers are flooding the market with all sorts of new assets and strategies: single-stock ETFs, leveraged and inverse ETFs, and even spot Bitcoin ETFs can all be accessed from your brokerage account with the click of a mouse.

You don’t need any of that: Basic stocks and bonds remain the mainstay of real long-term investing, and accessing them through tax-efficient ETFs has never been easier or cheaper.

Combining these in the right proportions is another challenge. Complex mathematical models that derive the “optimal” portfolio seem like one solution, but they can create a false sense of security, since predicting the future with any degree of accuracy is very difficult.

These complex tools still offer some insight. They point to simple, timeless principles that every investor should understand. Portfolio construction, after all, is based on a few fundamental ideas that have stood the test of time. Investors need to take on enough risk to achieve a rate of return that will meet their objectives. And there are two asset classes that can help align the appropriate risk and return: high-risk stocks and low-risk bonds.

Smart People

Portfolio construction is ultimately about combining different assets to achieve a desired rate of return, level of risk, or both. In its ideal form, it seeks to either minimize the risk required to achieve a desired rate of return or maximize the return for a given level of risk.

Diversification plays a big role in achieving that goal. Diversifying your portfolio means holding multiple assets with uncorrelated performance so you don’t lose your entire portfolio when things get tough. Understanding how much of each asset you need to realize maximum gains is key.

The late Nobel Prize-winning economist Harry Markowitz is credited with formalizing the mathematics behind portfolio construction. His models, still used by many financial professionals today, calculate the exact ratio of stocks and bonds needed to achieve the ideal portfolio — one that maximizes returns for a given level of risk.

The math behind Markowitz’s framework is complex and too complicated for most people to understand, but it’s based on a few simple concepts that can help any investor make better long-term investment decisions.

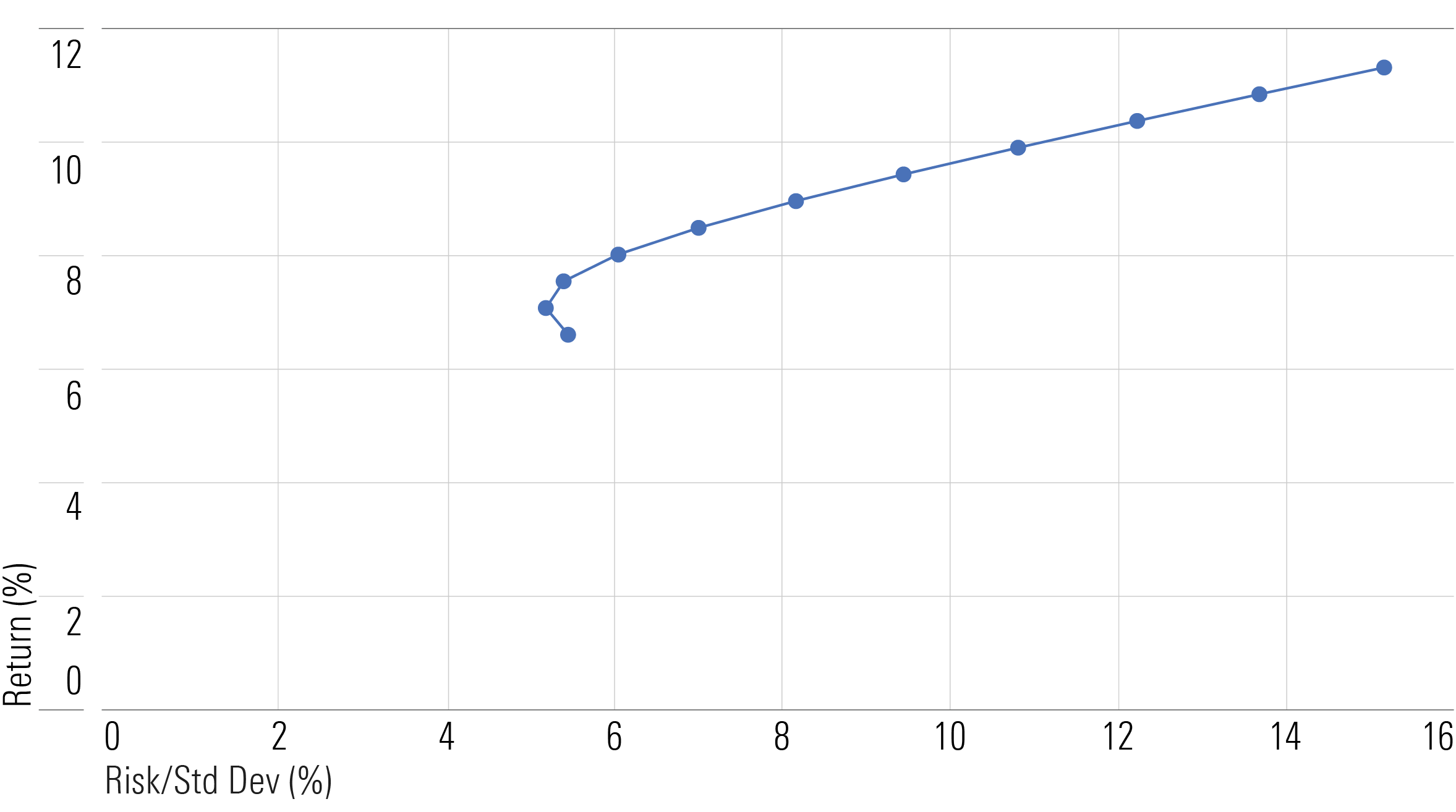

Figure 1 is a graph showing the output of Markowitz’s model, commonly referred to as the “efficient frontier.” The graph shows the different combinations of U.S. stocks and bonds that produced the highest returns (vertical axis) for a given amount of risk (horizontal axis). The points on the far left of the graph represent a low-risk portfolio of 100% investment-grade U.S. bonds (approximated by the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index), while the high-risk portfolio on the far right is U.S. stocks only (approximated by the S&P 500). The points in between represent various combinations of these two assets.

Without reading too much into the numbers, it’s easy to draw the conclusion: To increase your rate of return, you need to take on more risk – that means holding more stocks and fewer bonds. And there are subtle differences between the two ends of the chart: the least risky portfolio is not one allocated entirely to bonds. With a small investment in stocks, the most risk-averse investor can reduce risk even further by holding riskier stocks. On the other side of the chart, the most aggressive investor can reduce risk significantly with only a small impact on long-term total return.

Drawing more precise conclusions about the exact allocation requires some caution. It is easy to assume that sophisticated mathematical formulas and the precision of the allocations they derive will give precise answers about the future. But this is not the case.

Garbage in, garbage out

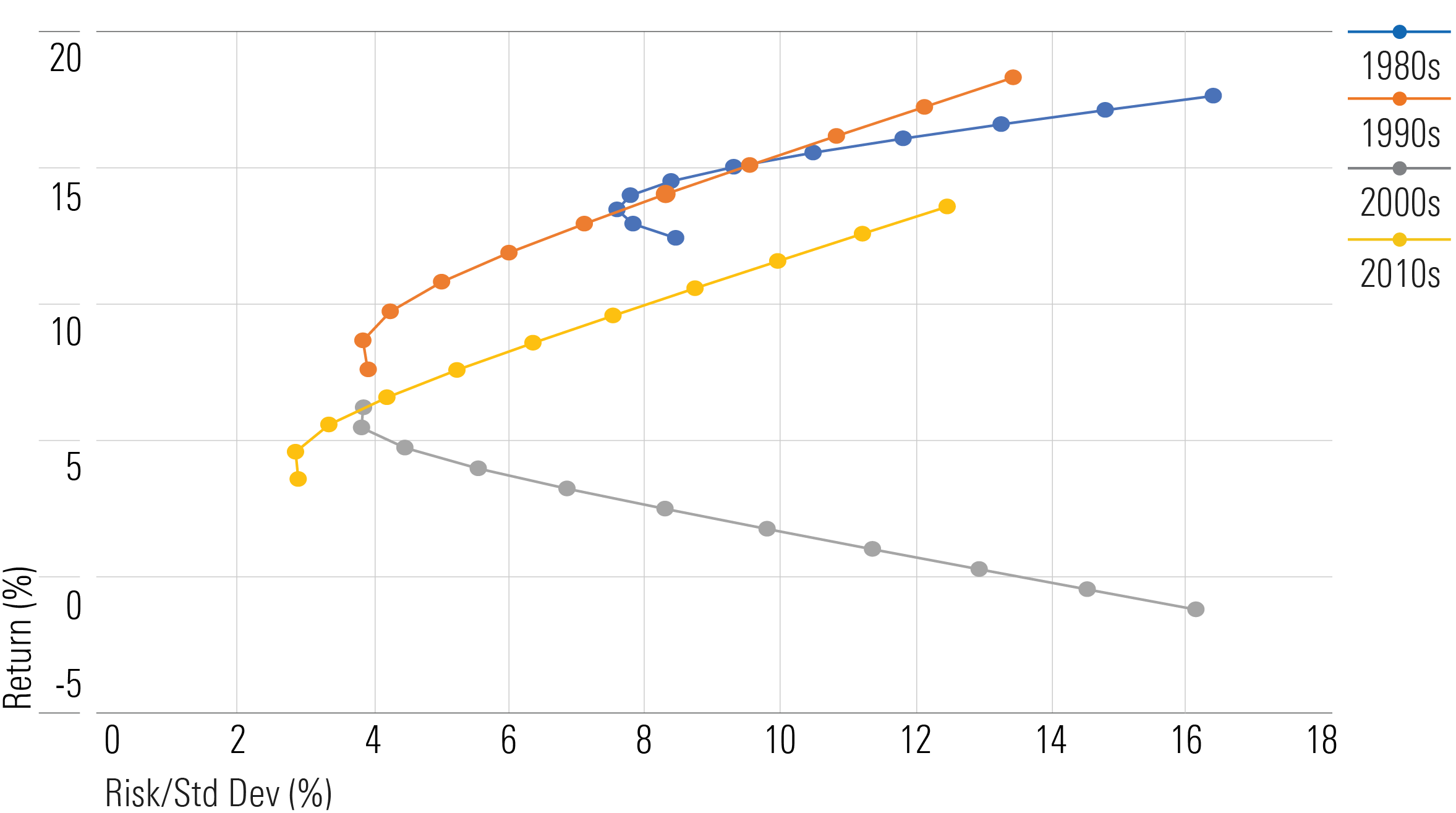

First, let’s consider what’s going on behind the scenes. Figure 1 was constructed using historical numbers, and the future is unlikely to be exactly like the past. Returns, volatility, and the relative movements of stocks and bonds change over time. Those dynamic trends cause optimal allocations to fluctuate, sometimes dramatically. Figure 2 shows that the efficient frontier can change substantially from one decade to the next. Thus, using historical data to predict optimal allocations in the future can have disastrous results.

Accuracy is not one of the Markowitz model’s strengths, which doesn’t make it completely useless, but it does provide valuable insights for constructing long-term investment portfolios.

First, stocks and bonds move differently from each other. For the entire period in Figure 1 (January 1976 to October 2023), the correlation coefficient (a measure of their relationship with each other) was about 0.24. For reference, a coefficient of 1 means that the two move together, while a coefficient of 0 means that there is no measurable relationship between their movements. Assets with low correlation are desirable, which leads to portfolio diversification.

These conclusions would likely not change much if more asset classes were included, such as international equities. Figure 3 shows the correlations of the four major asset classes from January 2001 to May 2024. Equities, both domestic and international, were closely tied to each other, with correlations ranging from 0.7 to 0.9. Bonds, on the other hand, tended to behave very differently; their correlations with all three regional stock markets were quite close to 0.

What does this mean? Allocating to different regions of the global stock markets did not provide much diversification benefit. International market stocks almost always move in the same direction as U.S. stocks, while bonds were the only true diversifier. In other words, amounts allocated to stocks and bonds can have a greater impact on a portfolio’s long-term risk and return than amounts allocated to foreign stocks and domestic stocks.

Don’t overcomplicate things

It is impossible to achieve an ideal portfolio because the future cannot be predicted with precision. Markowitz’s optimization model is very useful as a way to understand the mathematics of diversification. Its weakness is not in the mathematics. The model’s ability to correctly determine the optimal allocation directly depends on the accuracy of the predicted inputs.

Investment portfolios are almost always constructed to achieve a specific goal, determining the rate of return you require and the amount of risk you are willing to take (or are willing to take), so everyone has different preferences and different mixes of stocks and bonds based on their own circumstances.

On that note, Markowitz shared some valuable insights about how he approaches his portfolio.

“…I should have calculated the historical covariance of the asset classes and drawn the efficient frontier. Instead, I visualized my grief if the stock market rose sharply and I was not invested, or fell sharply and I was fully invested. My intention was to minimize future regret, so I split my investments 50/50 in bonds and stocks.”

Despite his deep understanding of the mathematics behind portfolio construction, Markowitz was humble enough to foresee his own behavioral weaknesses and chose his allocations to stocks and bonds accordingly. This may be his most important contribution to the financial world: the right portfolio is one that will help you achieve your goals and let you sleep well at night, regardless of the formula.