This risk does not arise primarily for political reasons, even though I have criticized the Chinese Communist Party in op-eds, interviews and books for the past 20 years. It is because I am the legal representative of a debt-ridden company registered in China. Under Chinese law, to close a company, you must pay several employees at least one year’s salary each. They are honest, hardworking people and they deserve their salaries. We are doing just that, paying them bit by bit. In the meantime, I could be banned from leaving the country until I pay off the debt.

Foreigners have been apprehensive about traveling to China since the Chinese government arrested the “two Michaels” in 2018, two Canadians who were held hostage to force the release of a senior executive from Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei who was being held by police in Vancouver. Like Russia, China has earned a reputation as a hostile country with a legal system subject to the whims of its political leaders. From the moment they cross the border, foreigners visiting China feel like they’re playing Russian roulette with their freedom at stake.

Most are concerned about political missteps. Have they written something that could be perceived as anti-China? Have they been quoted speaking negatively about the leadership? In fact, China has few formal rules about what foreigners (as opposed to Chinese inside the country) are allowed to say about the leadership. It would take a very high level of offense to provoke the authorities into action. Australian mystery writer Yang Hengjun was detained when he flew to Guangzhou in 2019 and subsequently jailed for three years and given a suspended death sentence, apparently for writing a pro-democracy blog (though he was also accused of espionage). But arrests of foreigners for political speech are relatively rare.

The most common reasons for foreigners being detained are commercial disputes and debts. If a foreign company owes a Chinese company or individual thousands of dollars, Chinese law allows the alleged creditor to arrest anyone connected to the company and hold them in a guesthouse or hotel with guards until the debt is paid in full. This is infuriating: the detained person often has no power to influence the company’s payment process. And even if the debt is paid, it can take months or even years for the detained person to receive official approval to return home.

Sometimes people with only tenuous ties to companies caught up in disputes are denied the right to leave China, a so-called exit ban. “Renminbi funds” (investment funds in China’s local currency) “react in an extraordinary way to these exit bans,” says an American friend who has been dealing with them for years. In March, The Wall Street Journal reported on an American who was trapped in China for more than six years due to a dispute between his company’s headquarters and its Shanghai subsidiary. Executives of major banks and asset management companies can be barred from leaving the country because of the debts of their client companies.

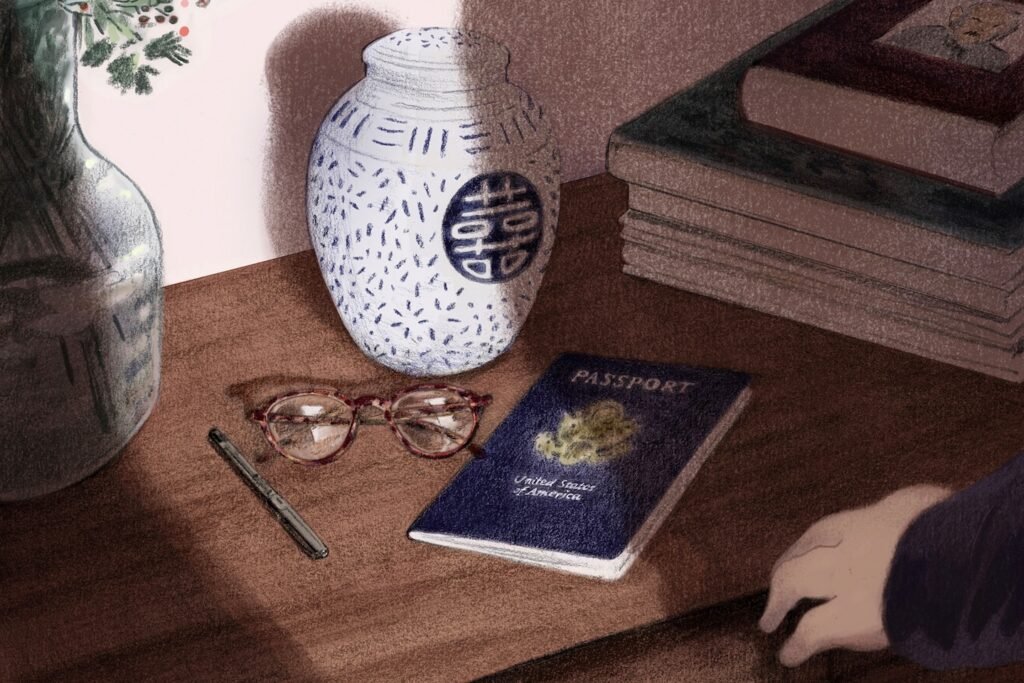

What’s particularly problematic about exit bans is that those subject to them often don’t know they exist: The State Department has said, “In most cases, Americans only become aware of an exit ban when they attempt to depart the United States.” [People’s Republic of China]”There is no reliable mechanism or legal process for finding out how long the ban will last or for me to challenge it in court.” Many Chinese companies are outraged by my company’s work to thoroughly investigate fraudulent public companies. Corruption is much more blatant at the local level than at the national level, and it is easier for large companies in small cities and towns to buy the complicity of the police and courts. If someone in a town in Hunan or Shanxi province, for example, were to persuade a local prosecutor to sue my company, I would never know about it and could be detained pending future legal action.

Family matters would seem to be something that should be shielded from the political climate that has chilled relations between China and the West, yet Beijing has long viewed immigration as a privilege reserved for the Chinese. China is one of the most closed countries on earth, with fewer than one million foreign-born residents (including those from Taiwan) compared to a domestically born population of about 1.4 billion, according to the 2020 census. It is no wonder that China treats foreigners as curious but dangerous beasts who need to be closely monitored to prevent them from corrupting the local population.

But China has been my home for nearly 25 years, and my in-laws and many friends are there. I want to be with them to mourn my husband’s death. I last visited China more than four years ago, just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. I’m an American by birth, but not being able to return home feels like an exile.