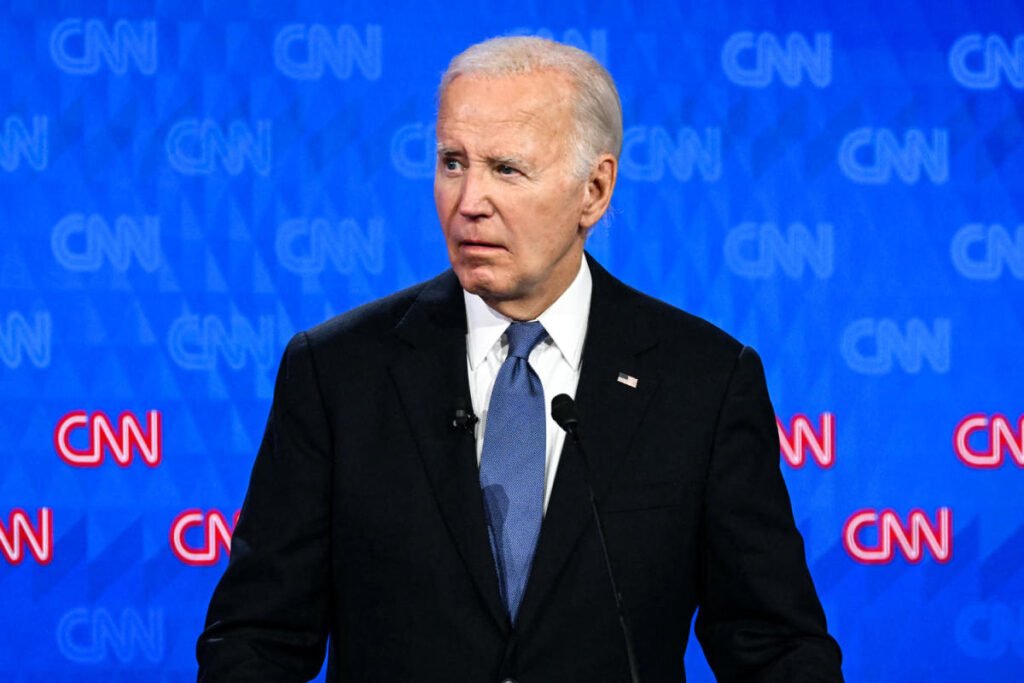

Inauguration as President Joe BidenFollowing Biden’s lackluster performance in the presidential debate with Donald Trump, Democrats are embroiled in a fierce debate over which candidate should replace Biden in the November 2024 election. But I learned another lesson from the debate: How is the United States dealing with an aging population? Despite progress on diversity, equity, and inclusion, ageism remains one of the last socially acceptable biases, ingrained in our culture, media, and institutions in not-so-subtle ways.

Aging is inevitable. It will strike us all, if we’re lucky. Even if you don’t experience the signs of aging yourself, you can almost certainly count on someone you know or a family member to do so. Yet, as a society, we portray aging as something to be feared and avoided, reinforcing negative perceptions that lead to the marginalization of older adults. This includes our elected leaders. At the same time, society is promoting increased longevity and life expectancy, evidenced by an entire industry based on the false idea that aging can be slowed with the right products, habits, and diet.

Our treatment of older Americans reflects a dire reality. We are unprepared for an aging society, with the number of people aged 85 and older expected to nearly quadruple between 2000 and 2040. By 2034, for the first time in history, the number of older adults in the United States will exceed the number of children under 18. This aging population creates several important societal dilemmas. Older adults have more chronic health needs, are more likely to be isolated, and are more likely to work and face discrimination in the workplace because of their age. As they age, they also become more dependent on their families. One in four family members serves as a caregiver, many of whom are unpaid. One in six older Americans face employment discrimination while seeking work, and two in three face discrimination after they are hired.

The symptoms Biden displayed during the debate were straight out of the medical textbook, common among older adults: slowed reaction time, difficulty finding words, etc. Combine that with lack of sleep and a viral illness or cold, and anyone over 40 is likely to suffer from similar symptoms: hoarseness, slowed reactions, confusion, etc.

This is not an apology for their debate performances, but simply a reminder that both presidential candidates are, simply put, older. With older age, some disability is to be expected: a bad cold, a potentially fatal hip fracture, a heart attack that leads to hospitalization. To dismiss our society’s desire to cave in to ageism and our own amnesia about the effects of aging is completely misguided.

Historically, the age of the U.S. president has been a subject of debate and scrutiny, with concerns often raised about his or her physical and mental ability to handle the rigors of the presidency. Ronald Reagan Reagan became the oldest president at the time when he was inaugurated at age 69 in 1981. Questions about his age and cognitive abilities intensified during his second term, when he began at age 73. Despite these concerns, Reagan served out his term and left office at age 77, setting a record for the oldest president to finish in office.

Since President Reagan, advances in medical technology, such as innovations in cancer treatments and heart medications, have increased life expectancy by several years for all adults, including white men, but COVID-19 has caused life expectancy to recede. In other words, we are living longer, thanks to science. The fact that the two oldest people ever ran for president is a sign of success and progress, even with the setbacks it brings.

Here we return to the paradox of age: our desire to live longer is difficult to reconcile with how society treats those who achieve it. Polling data suggests that a majority of voters doubt whether an older candidate could effectively fulfill the responsibilities of the presidency. For example, a Pew Research Center survey found that only 3% of Americans believe that the best age for president is 70 or older, with the majority preferring a candidate in their 50s. This concern is not unfounded, as cognitive decline can affect key aspects of presidential responsibilities, such as decision-making, memory, and the ability to cope with stress. However, it is also true that older age brings experience and wisdom, which are undoubtedly valuable assets for a president.

While there will always be disagreements, and the current debate is no exception, the conversation about aging need not become yet another source of division for us. Rather, it is an opportunity for reflection and greater compassion for older people, while at the same time acknowledging that we are intelligent enough to distinguish substance from appearance. Therein lies true common ground.

This article originally appeared on MSNBC.com.