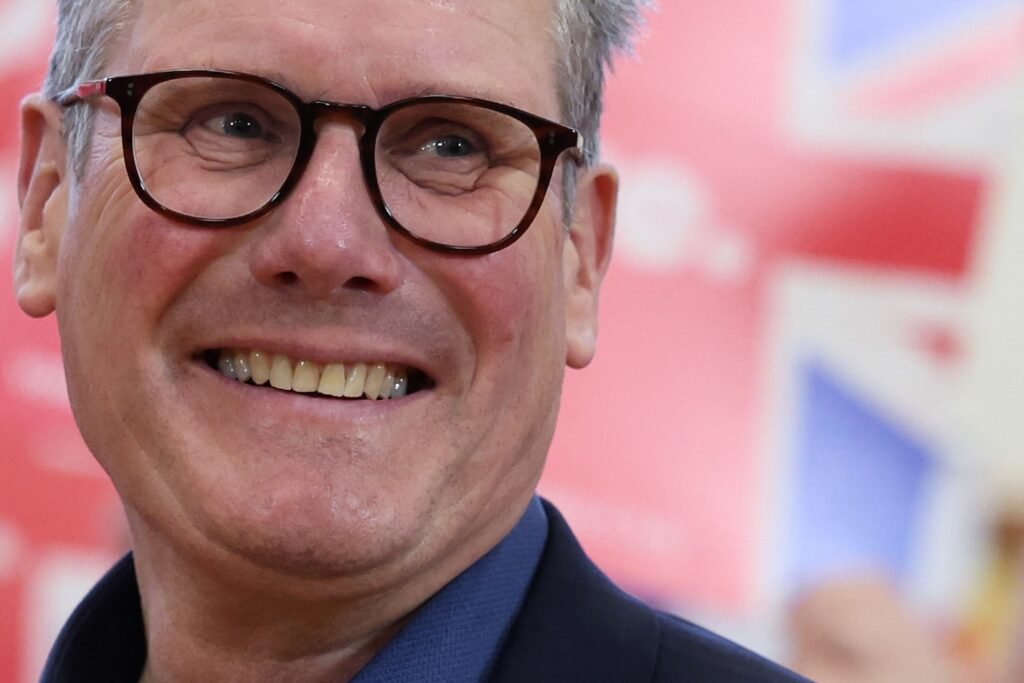

Starmer may be the most underrated politician to have won such a landslide victory. Since taking over as leader of Britain’s badly broken Labour Party in 2020, critics have said he lacked vision and charisma. They also accused him of tailoring his views to the political climate, fixating on everyday issues that matter to voters rather than big, galvanizing themes.

Most of Mr. Johnson’s perceived flaws turned out to be virtues his party needed and the country wanted. Former prime minister Boris Johnson was charismatic but voters found him unserious and too willing to bend the rules. Mr. Starmer, a tough-minded former prime minister who served as the country’s chief prosecutor, pitched himself as the antidote.

After radical Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party sank in the 2019 general election because of its ideological overreach, Starmer systematically purges the party, including Corbyn himself, while promoting moderate parliamentary candidates and filling key positions in the shadow cabinet.

Ideology has also proved a thorn in the side of the Conservative Party, whose approval ratings have been falling since the “Partygate” scandal came to light in which Johnson violated coronavirus restrictions. But during Liz Truss’ 44 days in office, when her radical tax cut proposals sent shivers through global financial markets, large swaths of the public abandoned the party altogether.

The outgoing Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, had a more fiscally conservative stance and this seemed like a reasonable fix, but his party was deeply divided and he proved ineffectual, and calling an early general election was his final miscalculation.

A safe hand has never looked so good. The rare endorsement of Labour by two of Britain’s most market-oriented publications, The Economist and the Financial Times, speaks volumes. Everyone wanted “change”.

If it was a mistake to underestimate Starmer before the election, it would be equally unwise to misjudge his chances of success.

Mr. Starmer’s challenges are certainly daunting. Unlike Tony Blair, who returned to power in a landslide victory in 1997 during an economic boom, Mr. Starmer is trying to fix a serious economic crisis. Faster economic growth was at the center of his election pledge, which is one reason he has won the support of far more businesses than is typical for Labour leaders.

He did not seek to win support on far-reaching policies. Instead, he campaigned on five popular but broad “missions”: high growth, safe streets, breaking down “barriers to opportunity,” making Britain a “clean energy powerhouse,” and making the Conservative austerity-hampered National Health Service “fit for the future.” He even scaled back his clean energy spending proposals to avoid exposing the Conservatives to accusations of fiscal irresponsibility.

But the modest nature of these promises suggests that Mr Starmer understands the challenge facing any progressive at a time of deep distrust in institutions, including government. And as a progressive who learned from Mr Blair and ran as a moderate, Mr Starmer also knows the limitations of Mr Blair’s old ways.

One of Starmer’s obsessions is winning working-class voters back to the Labour Party, which, like social democrats in other countries (and the Democratic Party in the US), has lost large amounts of its traditional lower-income supporters – a fundamental puzzle that both the left and the centre-left must solve.

“I grew up working class,” he told the party’s conference last fall, vowing to govern on behalf of “working people in parts of the country that have been ignored, overlooked and marginalized as sources of growth.” They have borne the burden of “unsettled times,” he declared, and promised to alleviate it.

President Trump opposed Britain’s exit from the European Union, which most Britons see as a mistake, but he has not promised that it can be easily fixed, and he understands that a more rational path toward European policy will take time and care to be re-established on both sides of the English Channel.

It’s a tough time for a politician who is moderate by temperament but progressive by ideology. The strength of the far right in France’s parliamentary elections this Sunday should serve as a warning. Many of the voters Starmer won on Thursday were loan voters, just as Johnson won a slim majority for the Conservatives in 2019.

Starmer recognised that voters in all democracies are skeptical of big, flashy promises. “People need hope,” he told the Financial Times. “But it has to be realistic hope.” This is a great starting point for those arguing for change.