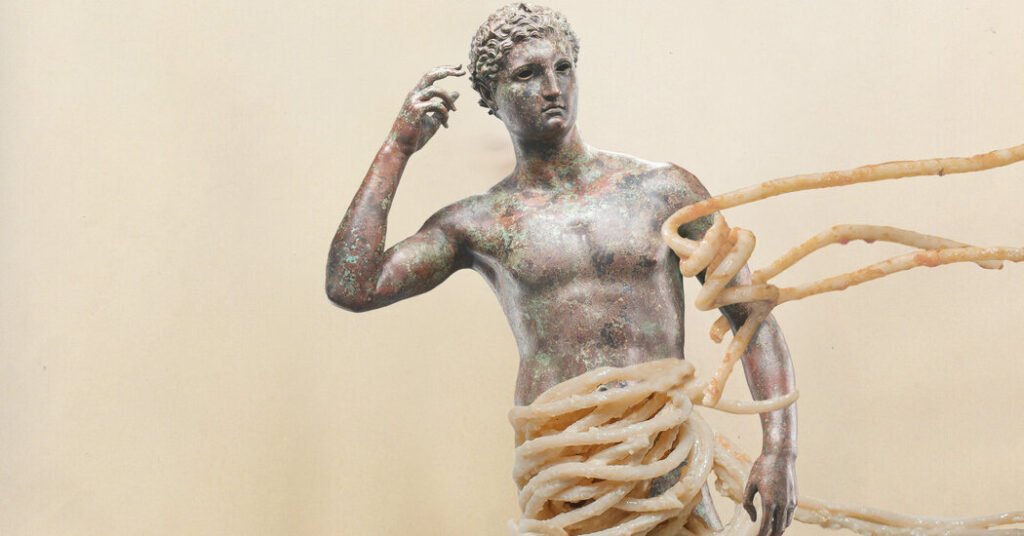

In the summer of 1964, Italian fishermen discovered an antique bronze statue on the seabed off Italy’s Adriatic coast. They brought it ashore in the small port of Fano, but the statue was missing for nearly a decade. Apparently it had spent some time in a monk’s bathtub or a cabbage patch. The statue resurfaced in the gallery of an art dealer in Munich, who dated it to around 400 BCE and claimed it was the work of the Athenian sculptor Lysippos. The Getty Foundation purchased it in 1977 for nearly $4 million and exhibited it as “Victorious Youth” in the Getty Villa, where it remains today.

But that may not be the case for much longer: In 2018, Italy’s Supreme Court declared the statue to be Italian property, acknowledging that it may have been found in international waters and that the sculptor was likely Greek.

Part of the reason was technical: the statue had been landed in an Italian port on an Italian-flagged ship and had been on Italian territory for several years. Part of the argument relied on historical interpretation: “It is highly likely that the artist had visited Rome and Taranto” when the statue was made, the judge said. He added: “Greece and Rome were on good terms at the time and Roman civilization subsequently developed as an extension of Greek civilization.” In the judge’s view, these considerations were sufficient to establish “important links” with Italy, a state that had only come into being in 1861. In May, the European Court of Human Rights upheld Italy’s right to seize the statue.

It’s judging time for museums. There is widespread agreement, even among museums, that questionable items in their collections should be returned. But to whom? If a statue cast in Greece 2,000 years ago is found off the coast of Italy, does it become part of modern Italian heritage? Italian courts seem to think so. If a statue cast in Rome 2,000 years ago is found in Greece, Cyprus or Turkey, does it belong to one of those countries, or can Italians claim rights to Roman artifacts on the grounds that they share a culture (whatever that means) with the ancient Romans? Is the modern Italian Republic the successor to a multi-ethnic Roman Empire that stretched across most of Europe, the Near East and parts of North Africa for more than four centuries?

These are difficult questions that may not have satisfactory answers. If an item is hundreds of years old, a museum cannot simply return it to whoever once owned it, and identifying the original owner or their descendants is usually not an easy task. The default response is to send the item to the ruler of the modern state within the borders of where the item was supposedly originally found. This can lead to inconsistencies.

Consider a recent case in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, where Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos, head of the office’s antiquities trafficking unit, presented to the Chinese consulate in New York 38 East Asian antiquities that his office had seized. Among them were what Kate Fitz Gibbon, executive director of the US think tank Council on Cultural Policy, described to me in an email as a “miscellaneous collection of Tibetan Buddhist objects,” some of which were “probably copies.”

Given China’s controversial record in Tibet, should Chinese authorities take possession of these sacred objects? In August 2023, when a New York collector donated the remarkable icons to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama wrote that he was “very pleased to learn that some of our sacred images have survived and are being treated with proper respect elsewhere.”

Other cases have raised questions about whether museums have a responsibility to ensure that returned items are properly cared for and displayed, such as the case of the Benin Bronzes, looted by the British in 1897 from Benin City, Nigeria, and exhibited in museums around the world. In 2022, the Smithsonian announced that it would transfer ownership of 29 Benin antiquities to Nigeria’s National Museums and Monuments Commission.

Dealia Farmer-Paelman, founder of the nonprofit Reparations Research Group, filed a petition to block the transfer, noting that Benin sold slaves to European traders in exchange for brass bracelets, some of which were likely melted down to be cast into bronze bracelets. She argued, unsuccessfully, that descendants of African slaves living in the United States would have an interest in the fate of these treasures.

When the bronzes returned to Nigeria, the story took an unexpected turn. The Nigerian government had been lobbying for the return of the bronzes for decades, but the current Oba (King) of Benin, Ewuare II, also claimed the bronzes as his private property. The Nigerian government had announced that the National Commission for Museums and Monuments would be in charge of all negotiations, and had assured any group wanting to return the objects that they would deal with a single authoritative negotiator representing the public interest. However, in March 2023, outgoing Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari declared the Oba to be the full owner of all Benin artifacts. “We were caught off guard,” a commission official told the BBC. Cambridge University has suspended plans to transfer 116 Benin artifacts to Nigeria.

Who should own the Benin Bronzes? The current Nigerian government? Or the private property of Ewuare, a direct descendant of a slave-trading Oba exiled to the British? Or a museum where the descendants of those who paid for the materials with their labour and lives to make the bronzes can enjoy them?

The desire to right historical injustices is noble — and certainly great museums have questions to answer about some of their treasures — but in their rush to right old wrongs, they risk committing new ones.

The Getty vowed to continue to defend its ownership of the statue “in all relevant courts.” The museum has a good argument to make: artifacts from ancient empires often passed through many hands, traveled long distances, and were traded by people speaking many languages. It is misleading to imagine them as symbols of modern nations that may have once been provinces of such empires. Meanwhile, major museums have the right, even the obligation, to preserve and exhibit antiquities they acquire in good faith. But they must also be responsible for ensuring that returned artifacts are cared for by responsible institutions and properly stored and exhibited. If museums fail to fulfill their duty of care, they can be held liable for cultural vandalism.

Adam Cooper is an anthropologist and author, most recently, of The Museum of Other People: From Colonial Acquisitions to Cosmopolitan Exhibitions.

The Times is committed to publishing Diverse characters To the Editor: Tell us what you think about this article or any other article. Tips. And here is our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section Facebook, Instagram, Tick tock, WhatsApp, X and thread.