CONCEPCION, Chile — The throbbing blast furnaces of a shrinking steel mill and the flaring flare stacks of an oil refinery mark the aging industrial landscape around Concepcion, in southern Chile, where a historic ceramics factory recently closed.

But just beneath the wooded hills overlooking the city on the Pacific coast lies a potential revival: This is where a mining venture called Penco, led by Toronto-listed Aclara Resources, plans to dig for rare earth elements, the unique elements needed to make magnets for everything from electric-car motors and wind turbines to Lockheed Martin’s F-35 fighter jets and MRI machines.

The $130 million Penco project could be a “quick win” for Western countries that need sustainably mined critical minerals from friendly jurisdictions, Aclara CEO Ramon Barua Costa said. AlabamaThe company and its Chilean partner, steelmaker CAP, have just reapplied for environmental permits which they hope Chilean authorities will quickly approve to get the first project modules up and running by 2028, after an initial application fell through.

Penco is part of a regional trend that is gaining momentum not only in Chile but also in Brazil to break up China’s near-total control over rare earths. As the United States seeks to shift its manufacturing away from the Asian powerhouse and global industry shifts to making new, greener products like electric vehicles, establishing a reliable Western supply chain for rare earth supplies is likely to become strategically essential.

Miners say the ionic clays and monazite rocks found in parts of Chile and Brazil contain rare earth elements ideal for making magnets. China has been criticized for its environmental practices in rare earth mining, both at home and in Myanmar, but emerging ventures in Latin America have pledged to mine the elements sustainably. Automakers from General Motors to Toyota and emerging magnet makers have been scrambling to Chile and Brazil to explore potential sources of supply outside China. Particularly attractive are South America’s heavy rare earth elements dysprosium and terbium, which are found in smaller quantities than the lighter rare earth elements found in the United States and Australia.

“Automakers used to shake hands and say goodbye, but now they want to hear more details,” said an executive at a South American mining company, requesting anonymity due to the sensitivity of the business. Alabama.

Increased appetite

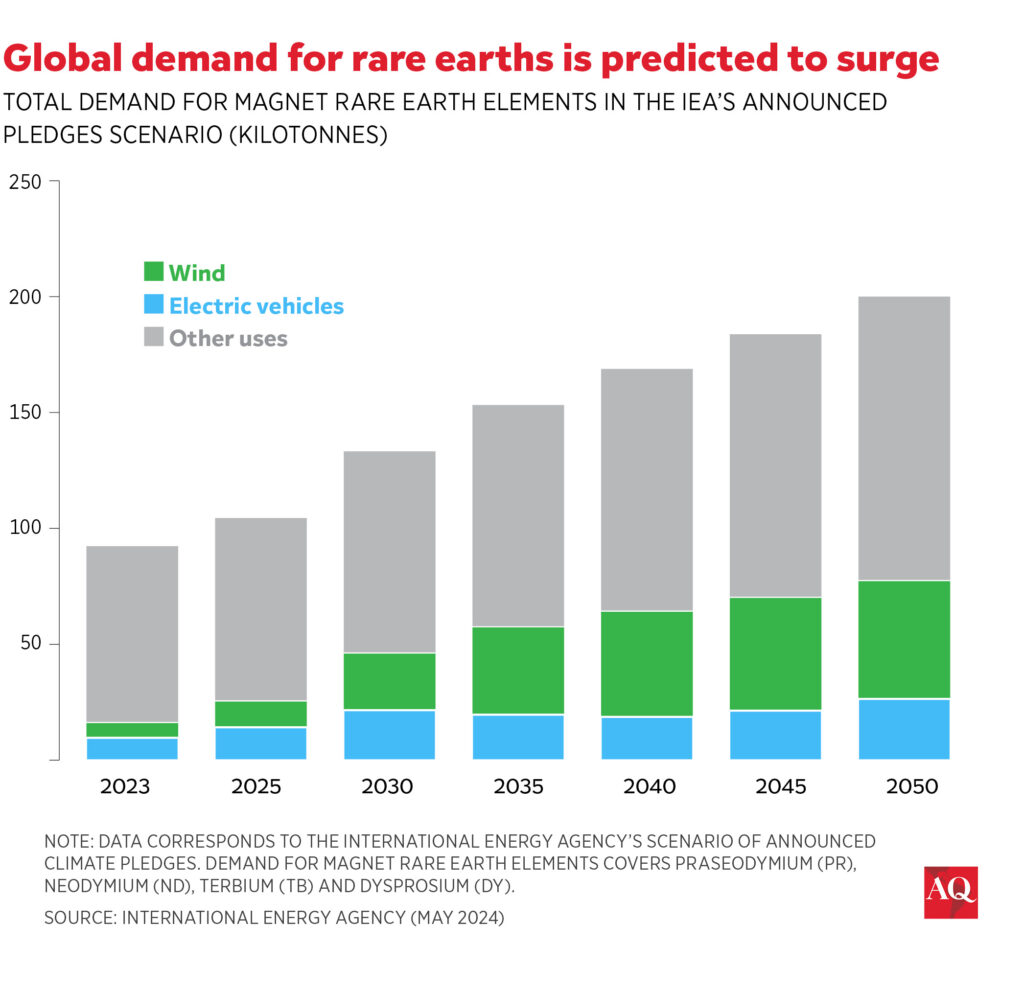

The data makes it clear why: According to a climate-friendly scenario published by the International Energy Agency (IEA), global demand for rare earth elements for magnets is expected to nearly double to 93,000 tonnes between 2015 and 2023, then grow by more than 80% to 169,000 tonnes by 2040, driven by EV motors.

The IEA said the world faces a lower risk of rare earth supply shortages than battery metals copper and lithium, which are abundant in Latin America, but rare earths are subject to “significant levels of geographic concentration” of current and future mining and refining projects, making “this market highly exposed to supply disruptions.”

But those fundamentals aren’t reflected in current rare earth prices, which experts say are kept artificially low by Beijing to produce more than 70 percent of the world’s supply and process more than 90 percent of it, making them too low for other suppliers to make a profit.

“At current price levels, most Western producers, and probably some Chinese producers too, are operating at a loss,” said Brian Mennell, CEO of Dublin-based tech-metals investment firm TechMet.

Brazilian rare earths

Despite government support, operations there have gotten off to a shaky start. In Goiás state, early mover Serra Verde Group, a venture controlled by U.S. private equity, has failed to ramp up production, and its woes have affected Chinese off-takers but could further hurt rivals by eroding investor confidence.

Serra Verde is modest about its business situation: “Serra Verde has been successful in getting across the starting line first, but it is still in an emerging sector and needs continued support to establish itself in a competitive market,” CEO Tras Moraitis said. Alabama By email.

Toronto-based Neo Performance Materials plans to buy 3,000 tonnes per year of rare earth oxides from West Perth, Australia-based Meteoric Resources’ Caldeira project in Minas Gerais state. The rare earths will supply a magnet plant Neo is developing in Estonia.

In neighboring Bahia state, Energy Fuels, a uranium producer based in Lakewood, Colorado, plans to mine rare earths in 2026. Mines in Brazil and projects in Australia and Madagascar will feed the company’s White Mesa, Utah, smelter, allowing it to monetize the radioactive materials that come with the rare earths. “Uranium is a problem for everybody else, but it’s a value add for us,” said Curtis Moore, a senior vice president. Alabama“It can be collected and sold to the nuclear industry.”

In Brazil, Aclara plans to replicate the Chilean project in Goiás state, while other contenders include APIA, Viridis and Brazil Rare Earths.

The situation in the United States

U.S. magnet manufacturing has not thrived, mainly due to China’s secrecy over its technological know-how and falling raw material prices. Chinese prices for dysprosium oxide have fallen 25% since October to just over $300 a kilogram, according to FastMarkets, a London-based price-tracking firm.

But with an eye on security of supply, Western governments are stepping in. The Biden administration is further increasing tariffs on Chinese high-tech products, including a 25% tariff on magnets in 2026. The Defense Department has awarded $430 million in grants to magnet manufacturers such as MP Materials, Lynas and VAC. It also aims to establish a domestic mine-to-magnet supply chain by 2027 to meet all defense needs, and is considering AI-based pricing of critical commodities. The US foreign investment arm, DFC, has opened an office in São Paulo with a mission to “expand its investment portfolio in key mineral resources,” as it already does with nickel.

For Latin America, rare earths are an opportunity to diversify and reinvigorate their economies in a more environmentally friendly way. The region can also fulfil its ambitious industrial ambitions by separating rare earths and processing them into metals and alloys. It is up to Western manufacturers, governments and investors to consider the fundamental value proposition behind this strategic resource.

tag: Critical Minerals, Mining and Rare Earths

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of American Quarter Or its publisher.