Washington

CNN

—

As the overwhelmingly conservative Supreme Court increasingly turns to history as a guide, a debate may be simmering over the extent to which the nation’s past can be used to resolve modern cases.

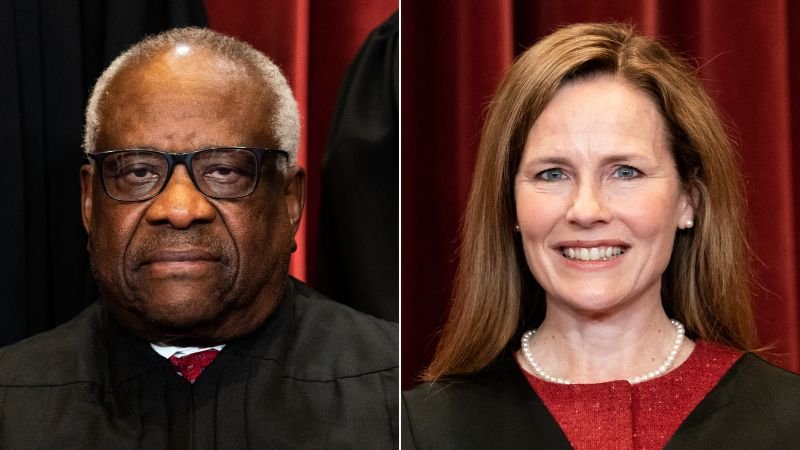

Justice Clarence Thomas’ unanimous decision in the trademark case last week sparked a fierce debate, led by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, about whether to use history to inform the ruling.

Justice Barrett, the court’s newest conservative, criticized Thomas, the court’s oldest justice, for being “laser-focused on history and missing the forest for the trees.”

The debate could signal a recalibration among some of the Supreme Court’s justices about when and how to apply principled law, a dominant legal doctrine among the court’s conservatives that demands that the Constitution be interpreted based on its original meaning.

Even a small change could have a huge impact on key Supreme Court cases, including a pending case that could have a major historical focus on determining whether Americans who are subject to domestic violence restraining orders can be barred from owning guns.

“Judge Barrett’s criticism of fundamentalism clearly illustrates the widening rift among the Supreme Court’s fundamentalists over how to properly use history,” said Tom Wolf, a constitutional law expert at the liberal Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School.

“It’s certainly possible here that an alternative approach to history, or multiple alternative approaches, could ultimately gain a majority,” Wolf said.

When the Supreme Court last week rejected a lawyer’s bid to trademark the phrase “Trump Too Small,” all nine justices agreed with that result, but there was sharp disagreement over the majority’s decision to invoke the country’s “history and tradition” to reject the trademark.

Barrett supported the court’s conclusion that a provision of federal trademark law banning the registration of a person’s name without the individual’s consent is constitutional, but filed a separate letter expressing discomfort with Thomas’s justification for the decision, which relied on “history and tradition.”

In her 15-page concurring opinion, Justice Barrett argued that the approach was “doubly wrong.” The court’s three liberal justices joined in part of her opinion.

In her decision, Justice Barrett acknowledged that “tradition has a legitimate role in constitutional adjudication,” but said the Court’s “laser-like focus on the history of this single limitation misses the forest for the trees,” poking holes in the history-and-tradition approach taken by Justice Thomas and other conservative justices who agree with his legal reasoning.

The late Justice Antonin Scalia, the Supreme Court’s leading advocate of principles, once described his approach to constitutional interpretation as “a piece of cake.” But the debates unfolding this term may be a recognition on the part of some on the court that history is often complex and nuanced and does not always yield easy answers.

“What we may see is a more nuanced approach to using history,” said Elizabeth Widerer, president of the progressive Constitutional Accountability Center.

“It’s a much more complicated issue, and the history is a much more contentious one,” Wideler said. “I think this debate between two conservative justices will shed a lot of light on the debate.”

Several court observers said it was premature to over-interpret the Thomas-Barrett debate.

“Barrett clearly believes that tradition is sometimes important, and she may differ with Thomas about when and to what extent,” said Ilya Somin, a law professor at George Mason University, “but there’s no clear doctrine here.”

The Supreme Court’s stance on history will be closely scrutinized in a landmark Second Amendment decision expected to be handed down in the coming days. In United States v. Rahimi, the Court must decide the fate of a federal law that bans people who are subject to domestic violence retraining orders from owning guns.

While most of the justices signaled they would uphold the law during arguments in November, the real challenge for conservatives is how to reconcile the ruling with a two-year-old precedent that said gun laws must have a historical connection to survive under the Second Amendment. In New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen, Justice Thomas wrote that modern gun control laws must be “consistent with the historical traditions of this nation.”

But at the nation’s founding, there were no gun laws that explicitly addressed domestic violence, so to uphold federal law, the court would at the very least have to explain how its standards apply to modern law.

06:50 – Source: CNN

Supreme Court strikes down bump stock ban

When Justice Thomas wrote the majority opinion in Bruen two years ago, Justice Barrett joined him in its entirety, but she also wrote a short concurring opinion in which she stressed the “limits to the permissible use of history” in deciding cases, including identifying historical dates that are necessary to determine whether a restriction is constitutional, Justice Barrett said.

In the months and years since the Supreme Court’s decision in Bruen, judges across the country have struck down a variety of gun laws using the “history and tradition” framework, while also confounding some legal scholars who point to obstacles that would come with the new rules.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor also noted these issues in her concurring opinion in the trademark case last week.

“The majority advised litigants and lower courts that a ‘historical approach'[h]”The ruling here, citing Bruen , is both sensible and actionable,” she wrote. “To say that such reassurance is uncomfortable would be an understatement. One need only read some of the lower court decisions that have applied Bruen to see the confusion this court has created.”

The Supreme Court’s two other liberal justices signed Justice Sotomayor’s concurring opinion, but Justice Barrett did not.

A new divide emerged last month in a lawsuit over funding for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a federal banking watchdog created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The payday loan industry sued the bureau, arguing that the way Congress funds it violates the Appropriations Clause of the Constitution.

Writing for a 7-2 majority, Thomas dug deep into pre-colonial British history and found that while Parliament had tight control over government finances, it “did not micromanage every aspect of the King’s finances.”

In other words, the legislature gave the king certain discretionary powers, and the executive branch’s discretion continued into the early days of the United States. Based on that history, the court has upheld the funding of modern government agencies.

But in a surprising dissenting opinion that drew support from both liberals and conservatives, Justice Elena Kagan argued that the Supreme Court’s historical analysis need not end with the late 18th century. Instead, she wrote, the Court can look to more modern times as a “continuing tradition” for determining the constitutionality of government policies.

Conservative Supreme Court Justices Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh joined Sotomayor in agreeing with this analysis, suggesting that even among conservatives who adopt this approach to their decisions, there may be differences in thinking about history and tradition.

“I see this as an evolving dialogue between essentially all of the justices on the Supreme Court, some of whom are certainly influenced by some very ignorant and deeply damaging opinions issued during their previous terms,” Wolf said, pointing to Justice Bruen and the Supreme Court’s decision two years ago overturning Roe v. Wade.

“Some justices clearly understood the substantive issues in their rulings and the methodological problems in relying on history as conclusive evidence in these cases at the time the courts handed down their decisions,” he added.

Thomas’ legal reasoning upholding the challenged provisions of the Lanham Act in the trademark dispute, Vidal v. Elster, broke new ground: It was the first time, Sotomayor wrote, that the Court had taken a history-and-tradition approach to deciding a free speech dispute.

Thomas noted the United States’ “long history” of maintaining restrictions on the trademarking of names, citing a series of cases dating back to the 19th century as well as precedents from courts outside the United States.

“I see no evidence that the common law affords protection to someone seeking to trademark the name of a living other person. On the contrary, English courts have recognized that selling a product in another person’s name is actionable as a fraud,” he wrote. “This recognition has been carried over to our country.”

Thomas’ arguments were joined by Kavanaugh, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch.

However, Justices Barrett, Kagan, Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson broke with those five justices.

In her concurring opinion, Barrett said the dispute could have been addressed based on the Court’s past trademark precedents, and stressed that relying solely on the country’s trademark history was not enough.

“In my view, the historical record alone is not sufficient to establish the constitutionality of this provision,” she wrote.

She further argued that even though the five-justice majority said in its opinion that it was not creating a new test, “the rule making tradition conclusive is itself a judge-created test.”