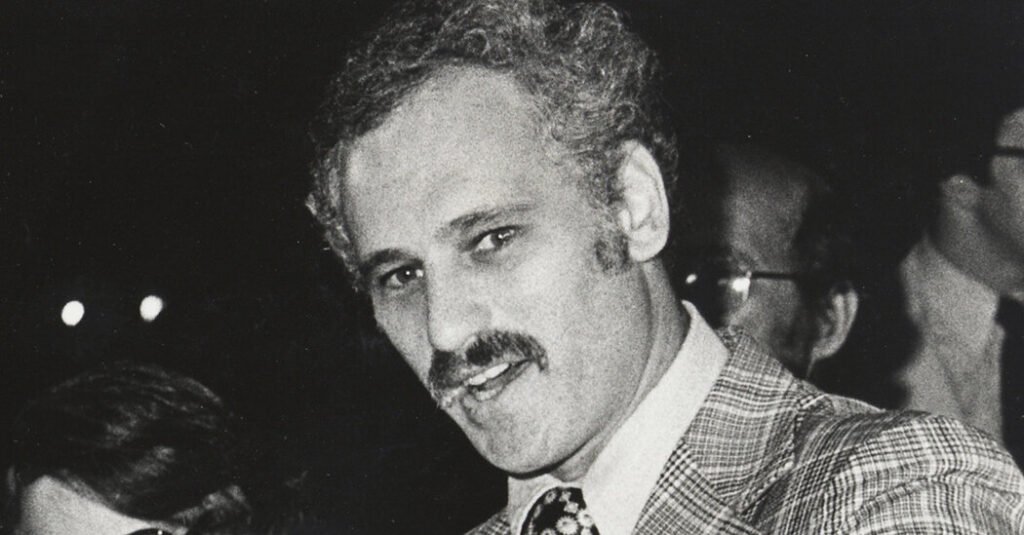

Neil Goldschmidt, a change agent in Oregon politics who transformed Portland into a vibrant, progressive, pedestrian-friendly urban center as mayor in the 1970s and later confessed to sexually abusing teenage girls during that time, died Wednesday at his Portland home. He was 83.

According to his family, the cause of death was congestive heart failure.

Goldschmidt served as mayor of Portland and then governor of Oregon from 1987 to 1991, and gained a reputation as a visionary architect of urban renewal. His ideas for making cities more walkable and less car-dependent became a model for city officials across the country.

In Portland, he opposed a federal plan to build a highway straight through the city, redirecting funding to build downtown parks and a light rail transit system, and he pumped money into revitalizing blighted neighborhoods, supporting mixed-use development that combined housing, retail and offices.

“He understood that attracting new families to older neighborhoods would provide labor and customers for downtown businesses,” Portland State University historian Carl Abbott said in an interview. “If downtown businesses are thriving and the downtown area is interesting and exciting, people are going to want to live there.”

After serving two terms as mayor, Goldschmidt was appointed Secretary of Transportation by President Jimmy Carter in 1979. After Carter left office in 1981, Goldschmidt joined Nike, one of Oregon’s largest companies, as a senior executive. In 1986, he was elected Oregon’s 33rd governor.

Seen as a rising star in national politics, Goldschmidt surprised political observers in 1990 when he announced he would not seek a second term and that he was separating from his wife, Margaret Wood, after 25 years of marriage.

Rumors of infidelity have swirled around Goldschmidt for years.

“Serving the state I love has come at the expense of another love, my family,” he said in announcing his decision not to run.

Goldschmidt founded a consulting firm and worked for the Oregon Commission on Higher Education.

Then, in May 2004, the scandalous 30-year secret was revealed.

The alternative newspaper Willamette Week reported that Goldschmidt, while he was Portland’s mayor, had multiple sexual encounters with the teenage girl over a three-year period, beginning when she was 14. The paper said he reached a financial settlement with the victim in 1994.

As Willamette Week was preparing to publish the story online, Goldschmidt confessed to a reporter from The Oregonian in a 50-minute interview, saying the girl, who lived nearby, was the daughter of someone who had worked on his mayoral campaign.

“I’m just living with this personal hell,” he said. “The lie has gone on for too long.”

He also acknowledged that the affair rumors were not just rumors.

“I think if people try hard enough, you can find indiscretions,” he told The Oregonian, “but nothing as ugly as this.”

The statute of limitations for any criminal charges against Goldschmidt, including statutory rape, expired decades ago. Women who were abused by him later gave a series of interviews to Oregonian columnist Margie Boulet about their relationships with the mayor.

The woman said the abuse began when she was 13, on her mother’s birthday. She said the abuse nearly destroyed her. She attempted suicide at 15 and then became addicted to alcohol and cocaine. She died in 2011.

“I had a lot of potential,” she told Ms. Boulle. “I was very smart. I loved to read. I loved to learn.”

Neil Edward Goldschmidt was born on June 16, 1940, in Eugene, Oregon, the son of Lester Goldschmidt, an accountant, and Annette (Levin) Goldschmidt.

After earning a degree in political science from the University of Oregon in 1963, he moved to Washington, DC, and worked as an intern for Senator Maureen B. Neuberger of Oregon.

Goldschmidt left Washington a year later and moved to Mississippi to work on voter registration drives with Charles Evers, brother of civil rights activist Medgar Evers.

After a few months in the Deep South, he enrolled in law school at the University of California, Berkeley, graduating in 1967. Instead of joining his classmates earning high salaries at major law firms, Goldschmidt worked for the Legal Aid Society in Portland.

He was elected to the city council in 1970. He was elected mayor in 1972 and served two four-year terms.

Mr. Goldschmidt married Diana Snowden in 1994. He is mourned by her, his children from his first marriage, Rebecca McMillan and Josh Goldschmidt, his stepchildren Kirsten and Neilan Snowden, his brother Steve, and eight grandchildren.

After his confession, Goldschmidt spent the rest of his life out of the public eye.

“Although he battled numerous health issues for many years, he remained active in discussions with family and friends about school, business, politics and wine until the day he passed away,” the family said in a statement, adding that they hope people will remember “the tremendous contributions he made to our community.”

Oregon politicians have struggled to define his legacy.

“When you think about what Neal accomplished and the impact he had on this state, he’s one of the political icons of the last 50 years,” Angus Duncan, a former aide to Goldschmidt, told The Washington Post after the sexual abuse allegations came to light. “He was a larger-than-life figure who left a lasting impact on this state.”

After his death, the reviews were less gracious.

“Neil Goldschmidt’s abuse of this young girl has destroyed her life, and this horrific act should render any other discussion of his political career moot,” Sen. Ron Wyden, R-Oregon, said in a statement. “The best response to this news would be to donate to organizations dedicated to preventing sexual abuse, like the Oregon Society for Sexual Abuse Treatment and Prevention.”