“Investors globally are turning away from sustainably-focused equity funds as poor performance, scandals and attacks from US Republicans have dampened enthusiasm for a much-anticipated sector that has attracted trillions of dollars in assets,” a Financial Times report said.

ESG is more of a mirage than an investment bubble, and its influence is so great that a Bloomberg Intelligence report earlier this year predicted that global ESG assets would exceed $30 trillion by the end of 2022 and reach more than $40 trillion by 2030. While the withdrawals so far may not seem huge in comparison, the tide of public opinion appears to have turned.

It was flawed from the start: ESG is too vague, allowing myriad interpretations of what the term means and allowing countless companies and other entities to claim to comply with vaguely defined standards.

All they had to do, it was suggested, was to promise to respect the environment, keep (undefined) social obligations in mind, and practice good corporate governance in running their companies, and they would win approval not only from the UN, but also from the company’s shareholders and even the stock market.

This would contribute to environmental sustainability while also enhancing the image of capitalism overall. What’s not to like about a system that seems to promise good public relations results in exchange for minimal commitment and expenditure?

Getting the corporate sector to commit to good behaviour across a range of goals, including sustainability and the environment, is not the same as directing investments towards clearly defined climate targets such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The financial sector’s energies would be better directed towards the latter.

Instead, investing in ESG stocks and funds, fuelled by the flow to exchange-traded funds, has come to dominate the sustainability world at the expense of other approaches – so far.

Even before his recent withdrawal from equity funds, ESG had become so associated with “woke” capitalism that BlackRock CEO Larry Fink rejected using the term, saying it was too “politicized,” though he continues to support sustainable investing principles.

The money that has flowed into ESG funds from institutional and retail investors, primarily benefiting the fund management industry, might have been better directed towards other forms of sustainable investing, many of which exist.

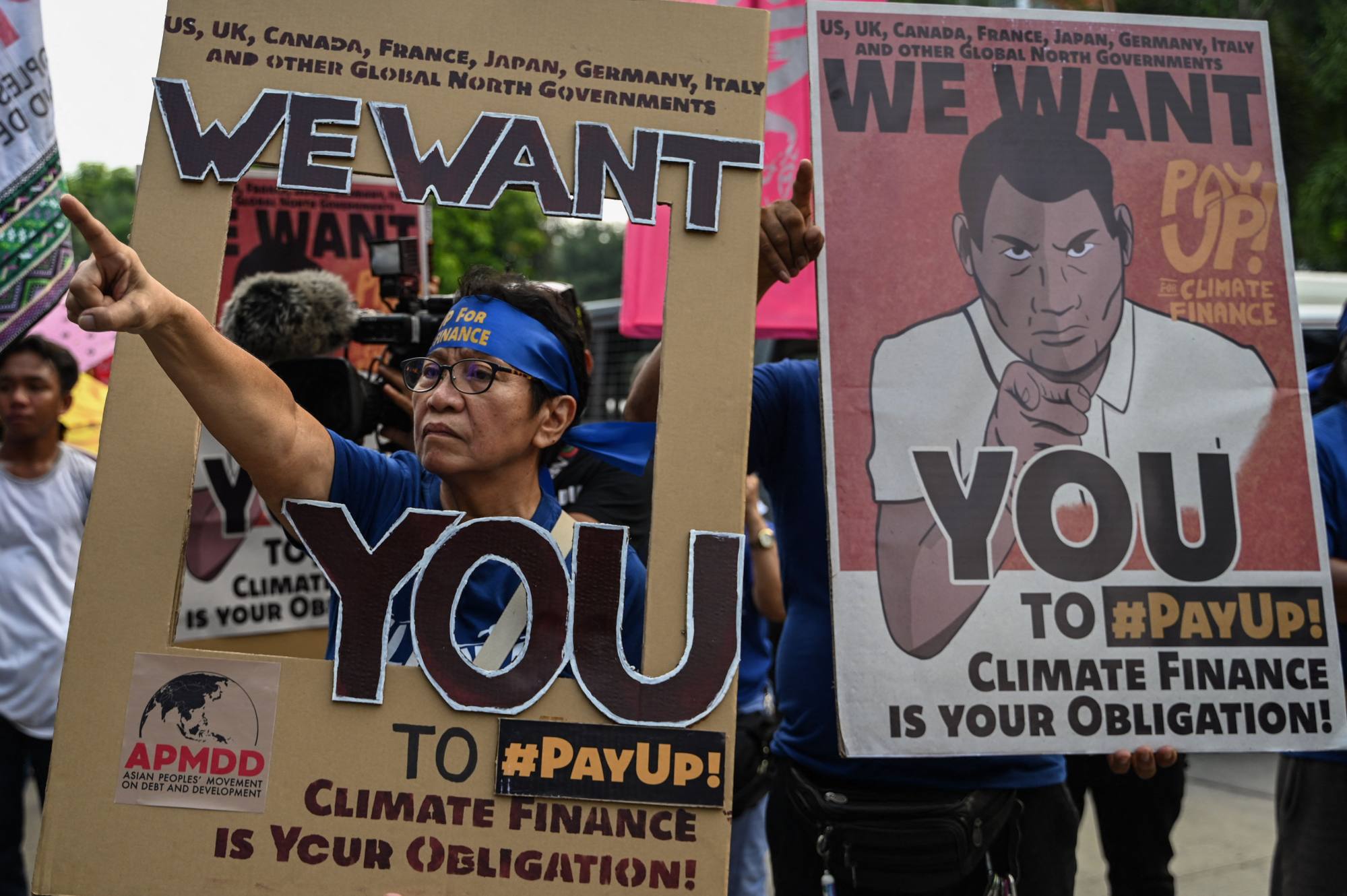

After all, market-based solutions will not work without public intervention to determine where the spending needs to be, how much is needed, and how investments should be structured. Fortunately, multilateral development banks are starting down this path by agreeing to coordinate efforts on climate change.

But this is not enough: they need to be given more capital and the authority to identify and fund projects at an early stage, before they are packaged and securitized for sale to the market.

This may help us avoid reckless initiatives like ESG, which could lead to trillions more dollars being wasted. Either way, this will be a hit to investors’ and taxpayers’ wallets, so they should pay attention.

Anthony Lawrie is a veteran journalist specializing in Asian economic and financial issues.