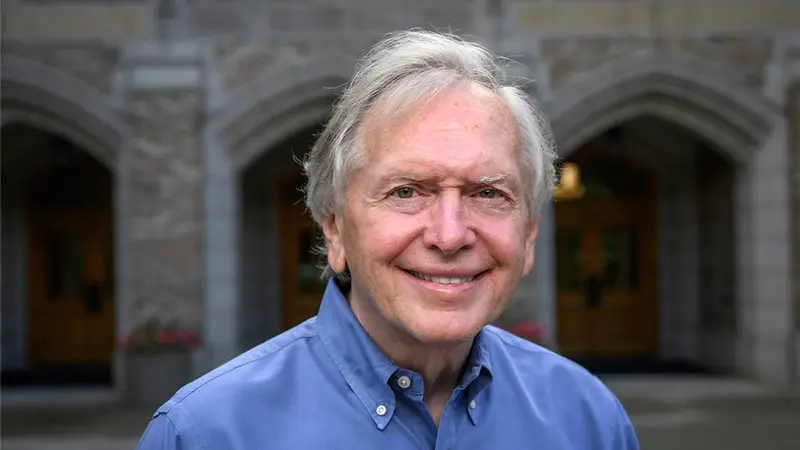

When we hear the word entrepreneur, we often conjure up images of tech titans like Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk, but the reality is less glamorous, according to Michael Morris, a professor at the McKenna Center for Human Development and International Business in the Keough School of International Affairs at the University of Notre Dame.

In fact, the majority of ventures around the world are started by people from poor or disadvantaged backgrounds, especially those operating in the informal or underground economy, Morris said.

While data on such ventures is scarce, Morris noted that they can account for a significant share of economic output, even in developed countries.

He went on to explain that there is a growing body of case study evidence supporting the idea of entrepreneurship as a path to economic independence for disadvantaged people.

Yet poverty is complex and goes beyond a lack of income to include food insecurity, unemployment or underemployment, health problems, poor schools, physical and mental exhaustion, poor housing and various forms of social exclusion and discrimination.

These barriers pose unique challenges to doing business, and when grouped together by type — literacy gaps, deprivation, major obstacles outside of work, lack of financial security or a safety net — they amount to what Morris calls “poverty liabilities.”

This disadvantage of poverty, on top of the usual disadvantages of newness and smallness that all entrepreneurs face, makes it much more difficult for disadvantaged entrepreneurs to start and grow their businesses than their more advantaged peers.

To address this, Morris, an entrepreneurship expert who has run successful venture programs at multiple universities, founded the Urban Poverty and Business Initiative soon after arriving at Notre Dame in mid-2019.

Since then, the effort has expanded to 38 cities, including South Bend, where the Entrepreneurship and Adversity Program aims to help people facing economic or other hardships start and grow businesses as a path to economic stability.

“What’s unique about our approach is that we break down the journey to a sustainable company — one that can improve the economic situation — into 80 stages,” Morris says. “The overall motto is that progress begets progress.”

He defines “sustainable” as steady gains over six months.

“The program works.”

Run with support from Susan McDonald, workforce development and global business program manager at the McKenna Center, the 10-month program takes a holistic approach to community empowerment, offering six weeks of in-person learning, individualized consulting with faculty, students and others, mentoring from successful local business owners, quarterly forums, online platforms and access to loans, grants and other resources through other formal and informal methods of communication and engagement.

The program also includes a research and tracking component, allowing Morris and his team to document the challenges facing existing and aspiring entrepreneurs, track their progress and identify ways to help them move forward.

To that end, Morris recently authored an article in Business Horizons that documents the phenomenon of underprivileged entrepreneurs’ fear of success and offers solutions to the problem, and is co-author of studies on misconceptions and errors of poverty entrepreneurs, overcoming the burden of poverty, poverty and entrepreneurship in developed countries, and entrepreneurship and poverty.

By engaging members of disadvantaged communities with students, faculty and staff and vice versa, the Entrepreneurship and Adversity Program supports the University’s Strategic Framework on Community Engagement and Poverty, a key area of focus as the University charts a path to success over the next decade.

Additionally, the program encourages community members who may feel alienated from Notre Dame to see the university as a partner committed to their success.

“The whole mantra is that progress begets progress.” –Mike Morris

“We emphasize that we are committed to the common good,” Morris said, referring to the university’s mission and Catholic social teaching more broadly. “With programs like this, we’re directly impacting real people with real solutions. And that’s important, because I think there’s increasing pressure on universities across the country to be more relevant to society and not just ‘ivory towers.'”

Now in its sixth year, the program serves as many as 70 people a year, including formerly incarcerated people and refugees — about 95 percent are people of color and about 70 percent are women, according to Morris — and has a long waiting list.

There are many success stories.

Coffee roaster Importin’ Joe’s started by selling coffee at the South Bend Farmers Market. Today, its specialty Ethiopian Java is sold in North and South Dining Halls on campus, as well as in dozens of retail stores across the country. Local catering company Soulful Kitchen is one of only four officially recognized catering companies on campus. This group includes such established companies as Levy, the food service provider for Notre Dame Stadium, and Three Leaf Catering, the university’s in-house service.

Overall, the program has supported more than 300 entrepreneurs and helped launch nearly 200 small businesses, encouraging underserved people and communities while growing the local economy in a way that supports and fosters a strong, innovative entrepreneurial ecosystem.

“The program works,” Morris said. “Both input and outcome measures suggest a fairly high success rate.”

It also helps that South Bend has a strong history and enterprising spirit, epitomized by names like Studebaker, Oliver, Bendix and Birdsell, he added.

“For a city that’s not that big, we’re finding a very rich talent pool of people who dream of owning their own business,” he said. “The interest is huge and it’s not dwindling.”

open the door

Luckisha Hunt of Mishawaka completed the program in 2022, toward the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hunt, a former social worker with a master’s degree in health care administration, is the owner of Heavenly Scent Sea Moss, which sells capsules, popsicles and skin care products made from the nutrient-rich algae found in the waters around St. Lucia in the Caribbean.

“This program was very helpful,” Hunt said, “It gave me a lot of information on how to actually go out and network and market my products. Everything I do now in business I owe a lot to this program.”

Hunt said she regularly recommends the program to others, adding: “I’m so grateful to Dr. Morris and Susan.”

Raymond Barber, owner of Ko’s Port-A-Pit Barbecue, also endorses the program.

“I always tell everyone I know who’s in business: ‘Hey, here’s Sue McDonald’s email. You better hurry up and email her, because it’s going to open some unbelievable doors for you,'” Barber said.

Barber, who grew up surrounded by kitchens and barbecues in South Bend and Kentucky, was recently brought on to mentor a successful local restaurateur as part of the second phase of the program — he completed the first phase, which consisted of six consecutive Saturday classes, in April.

“Each of the six sessions will give you a different way of thinking about what you want to do,” says Barber. “You’ll learn about fixed costs, variable costs, total fixed costs, contributions, margins, break-even or loss, products and what drives revenue.”

More broadly, the sessions, mentoring and other program elements “helped me have a bigger mindset about what I need to do and what my business means to me,” he said.

Like Hunt, Barber is based out of his home but hopes to eventually branch out and open both a food truck and a sit-down restaurant modeled after a classic barbecue joint.

He credits the Entrepreneurship and Adversity program for giving him the knowledge and confidence to pursue his dreams.

“When I look in the mirror, I see who I am and who my company is. It’s not just, ‘I’m Raymond Barber and, oh, I’m going to do this,’ it’s, ‘I’m Raymond Barber and I’m going to do this and I’m going to shine.’ The mirror gives me a drive that nothing else can provide.”

Broader impacts

The benefits go beyond just the individual.

Entrepreneurs who start out from disadvantaged backgrounds often fill niche areas that are ignored or overlooked by incumbents, Morris said. They’re also more likely to reinvest in their neighborhoods and communities, creating jobs and supporting and promoting other local businesses and organizations, creating a virtuous cycle.

“We don’t have empirical evidence yet, but my theory is that when you have enough entrepreneurs in an area, it makes the area more stable,” Morris said. “It brings social benefits like stabilizing crime, improving high school graduation rates. From a poverty standpoint, people don’t have a voice, but when they start having successful businesses, it gives them a voice and it helps address other issues that the community is concerned about.”

You can also share your hard-earned wisdom and knowledge with others.

“We have over 15 entrepreneurs in our classrooms every semester at Notre Dame, which is enlightening for our students,” Morris said.

Recognizing the value of this work, the St. Joseph County Community Foundation recently awarded the Entrepreneurship and Adversity Program $35,000 as part of its spring grant cycle. The Special Projects Grant will be used to support the SBEAP Collaboration Hub, a new drop-in center in South Bend.

“The Community Foundation of St. Joseph County is committed to improving the quality of life in St. Joseph County,” said Aaron Perry, the foundation’s vice president of community impact. “Partnering with the University of Notre Dame to advance entrepreneurial opportunities was a natural choice, and we look forward to the progress this effort will bring.”

Morris said the hub will open in late August and provide ongoing and expanded training, mentoring, consulting and other services to the more than 300 entrepreneurs who have participated in the program.

Reflecting on the purpose and significance of the project, he said, “It’s great to give Notre Dame a physical presence downtown and strengthen our programs while supporting entrepreneurs.”