Refusal is a powerful political act. Black people, especially Black women, have consistently rejected the conditions of oppression, discrimination, and dehumanization in order to protect themselves. Refusal is a powerful “no,” full of energy and meaning. “We refuse” is similar to Black colloquialisms such as “No,” “No way,” “Not today, Satan,” or my favorite, “Absolutely not.”

Resistance how Who responds to white supremacy? Why? To reject it. In America, there tends to be a focus on how resistance is expressed or enacted. There is not nearly enough emphasis on why resistance is so important to the American story.

My great-grandmother Ernesta tells me the story: In 1915, when she was 9 years old in rural Alabama, she stepped on a rusty nail. Soon after, an infection set in and Ernesta became very ill, probably with tetanus, which can be fatal if left untreated. My mother, Mary, panicked.

Mary took Ernesta to the only doctor she knew, a white man who lived in a large house on the other side of town. The doctor agreed to help Ernesta, but on one condition: after he cured her, she had to live in his house and work for his family for the rest of her life. Although slavery had been abolished 50 years earlier, the doctor felt entitled to Ernesta’s life and labor in perpetuity.

For a young black girl living during one of the worst periods in race relations in America, these were abhorrent but sadly expected terms. The contract the doctor offered included lifelong servitude and possibly more, a far cry from his vow to “first do no harm.” Mary panicked. Not wanting to send her daughter and only child to death, she agreed.

Thankfully, my great-great-grandmother, a former slave, stepped in. She refused the doctors’ unconscionable offers and picked up her sick granddaughter, carrying her home, where she administered a variety of natural remedies. Ernesta survived, but walked with a limp for the rest of her life. For me, this story has always encapsulated the power of white supremacy: choose a life of slavery, or reject it and limp. It wasn’t the doctors’ suggestions that shaped me, it was my ancestors’ refusal. Her answer wasn’t “no” but “absolutely,” a response that rejected the authority of white supremacy.

Refusal sets boundaries and defines unacceptable relationships as those that deny dignity, respect, and civility. It is not indifference or cynicism, but a commitment to living the full human experience. It is not about giving up the right to vote or ignoring the world. Refusal requires activism, traditional or creative, that advocates for freedom for all in ways that are acknowledged and celebrated by the LGBTQ+ community in June during Pride Month and by Black Americans on Juneteenth.

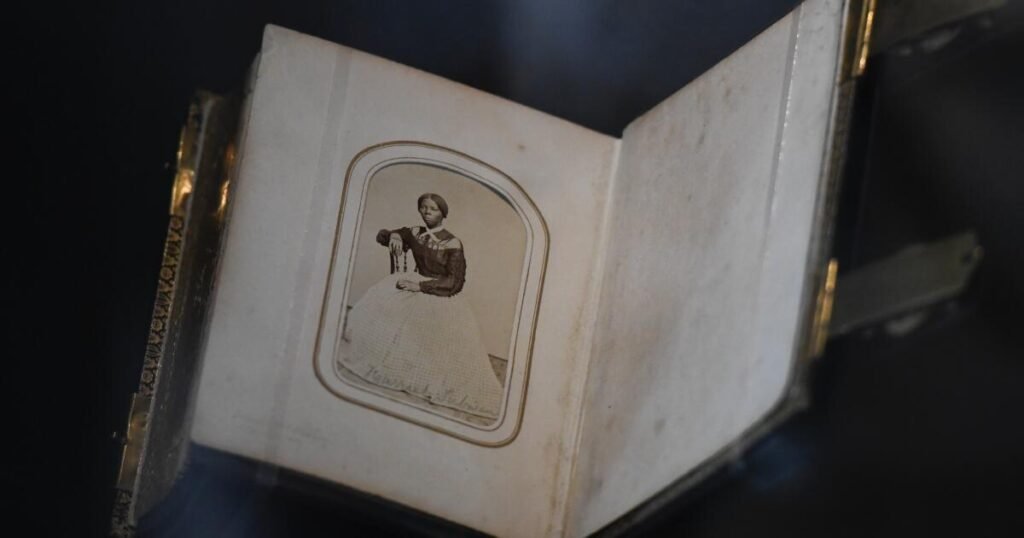

These efforts produced countless programs to feed, educate, heal, and care for black communities. Many key steps in ending slavery were acts of refusal. The Underground Railroad was created because abolitionists refused to be complicit in oppression and abuse. Black leaders and white allies formed protective societies and published newspapers, pamphlets, and personal stories that set out a national plan for abolition based on intellectual, rhetorical, political, and physical refusal. The approximately 250,000 black soldiers who fought in the Civil War had rejected slavery on American soil.

In a similar spirit, in the 1960s and ’70s, the Black Panther Party refused to be second-class citizens and launched nationwide breakfast programs, health clinics, emergency services, legal aid, schools and care programs to address the gaps in public services available to black Americans. In times of racial and political unrest, the Black Power movement focused on joy and unity, invoking hope, happiness and kinship as a shield against the demoralizing and corrupting effects of racism. James Brown’s “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” was a call to not let white supremacy dictate what is beautiful, what is inspiring and what is good.

Refusal can be individual, but it is collective in nature. That is why the sentiment behind the phrase “we refuse” is so strong among oppressed people. It is a key phrase in Black feminist and Native American politics, reiterating that oppressed people can and should refuse to be made invisible, silenced, or denied. From the arrival of slave ships in the New World, to slavery, segregation, and ingrained structural racism, Black people have always fought back.

And black culture refuses to be defined by oppression. Refusal is our anthem, our way of life, in the novelty and genius of our dialect, in the newspapers and literature we produced to tell our stories in the face of attempts to deny us our literacy. It is present in the drums and banjos and bass that permeate our music that refuses to be copied or erased, the vocals that refuse to be cowarded or watered down. It is even present in our traditions of forgiveness and hospitality in a society that often does not welcome us.

The revolutionary culture, art, and community that has arisen from these traditions are proof that, like my ancestors, we can forge new paths and refuse to choose between a life of bondage or a life of drag. We can refuse and insist on taking our destiny into our own hands, now and in the future.

Kelly Carter Jackson is chair of the African Studies department at Wellesley College andWe Refuse: A Powerful History of Black Resistance,Quote from “ X/Twitter: Follow