Sitting motionless for hours in a cold, bleak courtroom, unable to speak his mind and forced to listen to people say unpleasant things about him, Donald Trump sits in a dock in Manhattan Criminal Court, which may seem about as far removed as you can imagine from the cheering crowds and symbols of wealth that are his usual domain.

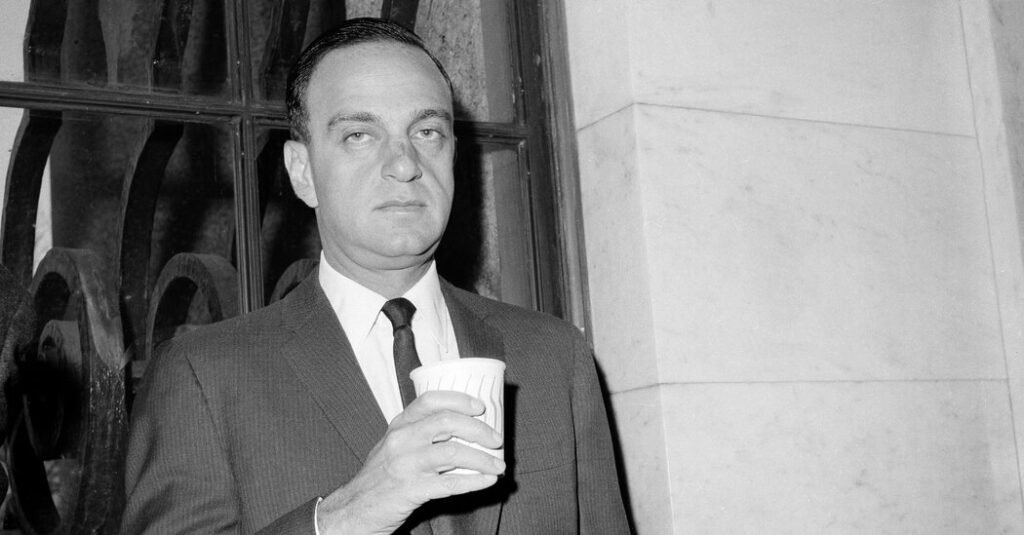

But it was in a different courthouse, just down the street, that Trump’s crafty mentor, Roy Cohn, pulled off one of his greatest legal feats. It was Cohn who taught Trump how to manipulate the law and other people to his advantage. His ghost now hovers over the former president’s legal opinions, influencing the case in ways big and small. The outcome of this trial may be the final verdict on Cohn’s masterful, wicked strategy.

Trump always admired Cohn’s bravery and combativeness. Cohn’s worldview seemed to justify the young developer’s crudest instincts. “If you want somebody to be mean, hire Roy Cohn,” Trump once said. His legal strategy boiled down to delay and denial, a willingness to attack judges and prosecutors (“I don’t care what the law is. Tell me who the judge is” was his most famous line), talking to the press whenever he had the chance, and intimidating and ridiculing witnesses.

Trump’s legal team has aggressively sought any delays and regularly called for mistrials or replacement of the judge. Of the four criminal cases Trump faces, the currently concluded one is probably the only one that will be tried before Election Day, which would all be undone if Trump wins a second term. Trump’s repeated attacks on Judge Juan Marchan and witnesses led to gag orders being issued and fines for repeatedly failing to comply with them. Trump also goes a step further than Cohn in filing lawsuits through the media; he founded his own social media organization, Truth Social, where he files his lawsuits.

In the Manhattan trial, defense lawyer Todd Blanche went after the bullshit bullet while cross-examining Trump’s former fixer Michael Cohen, shouting, “The jury doesn’t want to hear what you thought!” and quoting insulting comments Cohen had made about himself so closely that Judge Marchan reprimanded him for the profanity. Later, lawyer Susan Necheles tried to shame porn star Stormy Daniels, accusing her of “selling herself” and of having “a wealth of experience in making false sex stories look real.”

It was recently revealed that the former president has chosen not to take the witness stand and be cross-examined, instead waiting for a succession of prominent Republican senators to speak in his defense on the courtroom steps — a strategy that Cohn has stuck to.

Roy Cohn was indicted four times by legendary Manhattan prosecutor Robert Morgenthau. “I said to him, ‘Roy, tell me just one thing,'” Trump wrote in his book, The Art of the Deal. “‘Did you really do all that?’ He looked at me and smiled. ‘What do you think?’ He said. I had no idea.” The most infamous of these cases was the charge of conspiracy, extortion, blackmail and bribery of a former city appraiser inside the Foley Square courthouse. The trial lasted 11 weeks.

Cohn filed a formal affidavit with the judge, asking him to recuse himself from the case. He also argued that the indictment should be dismissed because it was motivated by a “personal vendetta” against Morgenthau. Both motions were denied, but served to slow the prosecution’s case.

On the final day of the trial, December 8, 1969, as Cohn’s lawyer, Joseph Brill, was about to give his closing statement, Cohn complained of chest pains and was rushed to the hospital. Court was adjourned with no known outcome.

The next afternoon, Cohn, dressed in a navy blue suit with a monogrammed shirt and thin stripes, surprised the judge and prosecutors by announcing he was ready to deliver his closing argument.

It was a clever strategy, effectively allowing him to testify in his own interests, which he had avoided, without being cross-examined.

He spoke brilliantly, without notes, for an hour that day, and an astounding seven the next day. Peter King, who would later become a member of New York’s congressional delegation, was there as a junior lawyer in Cohn’s office. “It was an effective, understated speech,” he told me last week. “It was emotional, but in a quiet way. There was no grandiosity. He seemed like the ultimate, perfect summation.” By the end, one female juror was moved to tears.

It took just four hours for the jury to acquit Mr. Cohn, who turned to the assembled reporters and said simply, “God bless America.”

Trump found his own ways to communicate with the jury, from refusing to respond to cross-examination, closing his eyes to block out testimony he couldn’t stand, and yelling abuse at the jurors while Stormy Daniels was on the stand.

Of all the lessons Trump learned from his mentor, the value of treating people as transactions may have been the most important. The former president had hired countless lawyers in his decades of litigation. Many were fired; some were never paid. But he held Cohn in high esteem, and he took his lesson to heart. In 1981, he gave his mentor a pair of giant diamond cufflinks as a sign of deep gratitude. A few years later, a friend of Cohn’s had them appraised. They were worthless fakes.

Kai Bird is director of the Leon Levy Biographical Center and co-author, with Martin J. Sherwin, of American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. He is currently writing a biography of Roy Cohn.

The Times is committed to publishing Diverse characters To the Editor: Tell us what you think about this article or any other article. Tips. And here is our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section Facebook, Instagram, Tick tock, WhatsApp, X and thread.