The St. Johns Bridge should have bike lanes, and it could have had them if advocates had sued the Oregon Department of Transportation nearly two decades ago when the agency missed a golden opportunity to provide adequate bicycle access after completing a major renovation.

I recently spent some time observing traffic on the bridge and was even more shocked by how unacceptably inaccessible the bridge is to anyone who isn’t in a car or truck. When I first shared images from that day on Instagram, the reactions reminded me of how many people share my concerns about what this bridge looks like today and my dreams for what it could become in the future.

Before sharing some of those answers, let’s remember our history…

advertisement

In 2003, ODOT began a major restoration project. They spent $38 million replacing and repaving the deck, repainting the towers, upgrading lighting, and more. But before ODOT restriped the lanes to the same four-lane, 40-foot-wide cross section the bridge had when it opened in 1931, it considered alternative plans. ODOT formed an advisory committee (which included representatives from bicycle advocacy groups, TriMet, freight operators, and more) and commissioned an engineering firm to analyze the options and write a report to inform its decision.

In 2003, David Evans & Associates published their report. And guess what? They determined that “there are no capacity constraints or operational deficiencies on the bridge that would prohibit the implementation of the striping option.” Central to this finding was that all roads leading to the bridge only have one lane in each direction and are controlled by traffic lights. Their analysis showed that while travel times across the bridge would increase (we don’t know the exact time), traffic volume would decrease and there would be no congestion on the deck.

But despite that study, and despite obvious safety concerns and requests for bike lanes that emerged during the City of Portland’s 2004 St. John’s/Lombard Plan, the nonprofit Bicycle Transportation Alliance (currently Despite complaints from The Street Trust and other pro-cycling groups, the Oregon Department of Transportation bowed to pressure from pro-freight groups and relined the road just as it has for the past 74 years.

advertisement

ODOT’s final decision on the striping plan came just a month after I started BikePortland, and I still haven’t done any research to fully understand what happened. But I know how it made me feel. May 12, 2005 My first post on this was published a few days after I heard the news, but you can feel my anger from the beginning.

The Street Trust also opposed the Odessa Transportation Authority’s decision, writing in an editorial posted on its website that “Under pressure from special interests, the Odessa Transportation Authority ignored the current facts. “The bridge will continue to be dangerous for the quarter of local residents who cannot drive.”

As my 2012 interview with former Oregon Department of Transportation Commissioner Matt Garrett revealed, the agency would not have been able to “develop road lines” without “the forces of the freight industry acting as ‘counter pressure’ on decisions.” It should have been possible to repaint it.

Portland residents tried to push back. Letters were sent to the Oregon Transportation Commission and even a naked bike protest was held, but the Oregon Transportation Commission ignored them all. They claimed that widening the existing sidewalks and making the alcoves larger would “improve bicycle safety,” but the truth then and now is that the sidewalks are not sufficiently engineered to allow cyclists to share them with pedestrians. It is said that the bridge is narrow and that riding a bicycle on the bridge is a frightening experience.

ODOT installed the shallows seven years later. While it’s nice to have more legal rights to drive on the road, a small speck of paint won’t do much to improve your blood pressure when drivers are coming at you at more than 35 mph.

advertisement

When Mitch York was killed by Joel Schranz in 2016, the Oregon Department of Transportation was asked to justify the lack of bicycle facilities on the bridge. A spokesperson for the Oregon Department of Transportation boldly claimed in an interview with local media that bike lanes cannot be installed because state guidelines require 19-foot-wide lanes for cargo trucks. This is a complete lie used by the Oregon Department of Transportation to justify a decision they know is not based on facts or engineering best practices.

As my 2012 interview with former Oregon Department of Transportation Commissioner Matt Garrett revealed, the agency would not have been able to “develop road lines” without “the forces of the freight industry acting as ‘counter pressure’ on decisions.” It should have been possible to repaint it.

Garrett’s remorse confirmed why many felt he should have sued the Oregon Department of Transportation for not complying with Oregon’s bicycle laws. The law requires the department to construct appropriate bicycle facilities whenever a road is rehabilitated. I’m not sure why they didn’t file a lawsuit, but I heard that they lost the case on technical issues and were concerned that the precedent could weaken bicycle laws in the future. remember.

We can’t change the past, but I will never forget ODOT’s role in putting us in so much danger on this bridge that I love and hate in equal measure.

advertisement

And judging by the reactions to my photos on Instagram, that same ambivalence exists among many.

“Even if you have great skills and are comfortable in traffic speeds,” Portland resident Ira Ryan wrote in an Instagram comment. She said: “Every time I cross a bridge, I still think it could be the last time… One look at a driver’s phone can kill a cyclist. It’s scary. ”

Another commenter, who said he crosses the bridge four times a week, said: “I’ve always wanted bike/pedestrian lanes on both sides…waiting for a truck’s mirror to hit me in the head.”

advertisement

One of our readers, Ben Guernsey, even created a conceptual design for how the lane configuration could be changed to make it safer for everyone.

I think Ben’s idea should be seriously considered, but the ultimate solution is to take freight transport off the bridge entirely. These large, noisy, smoke-filled trucks require their own bridge to keep them from passing through downtown St. John’s and dense residential areas. And that’s exactly what ODOT’s Westside Multimodal Improvement Study, which concluded late last year, recommended.

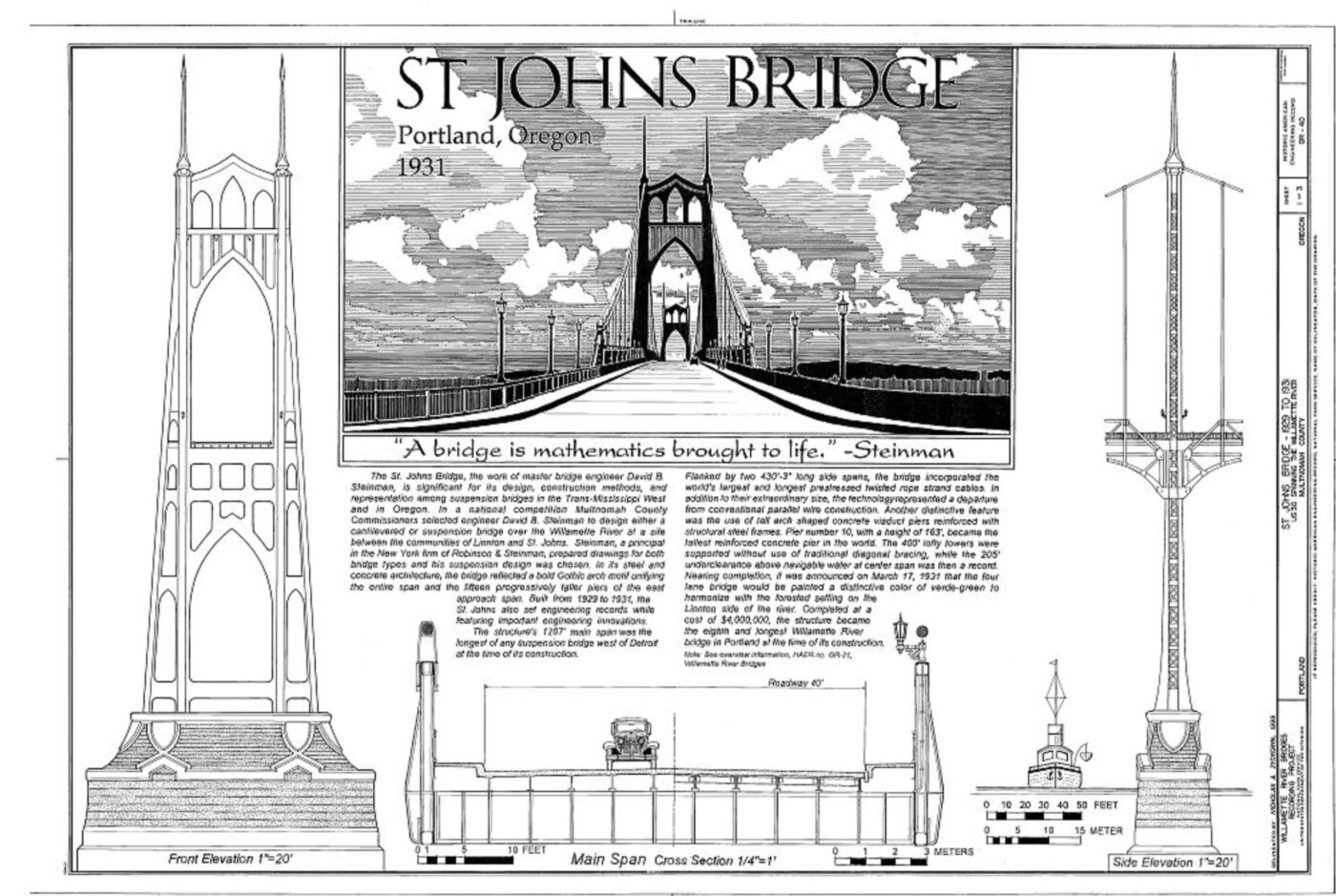

Whatever steps we take next cannot happen quickly. As these photos show, non-drivers can also enjoy the freedom of driving without fearing for their lives, shouting over traffic noise to be heard by their companions, or inhaling toxic exhaust fumes. There is a clear demand to utilize this beautiful and iconic bridge. By the bridge’s 100th anniversary celebration in 2031, we will be able to reimagine the bridge.