Irecent movie box office revenue civil war If any indication is any indication, Americans are preoccupied with the divisions within our country, which seem to grow wider by the day. But while futuristic or dystopian fiction stokes fear about our current state, history provides examples of how to heal broken bones. And the most hopeful parallels to our present come not from American history but from late 19th century France.

The Dreyfus Affair, involving the sale of military secrets to Germany and the bitter controversy over the guilt or innocence of artilleryman Alfred Dreyfus, tore France apart in the 1890s. But just when it looked like the discord might spark a civil war, the Prime Minister’s clever maneuvering pulled the country out of disaster and created a solution that avoided bloodshed. Even as the story of how France pulled back from the brink shows us that the United States needs to tackle the root causes of the problem more head-on, we have no idea how to overcome political hatred for the common good. will teach you many things. than the French did.

In the fall of 1894, the French Counterespionage Service discovered a document written by a French officer offering to sell military secrets to Germany. Suspicion soon fell on Alfred Dreyfus, the only Jew on the military staff. After a cursory investigation, Dreyfus was arrested and court-martialed. In violation of the Judiciary Act, prosecutors never presented evidence against Dreyfus to his lawyers, but a military tribunal quickly convicted Dreyfus.

He was forced to endure a humiliating public humiliation ritual in the church courtyard. Ecole Militaire. Dreyfus cried out as his insignia was torn off and his sword broken. “I am innocent!” Long live France! ” But his words were drowned out by the cries of 10,000 onlookers: “Death to Judah!”

read more: How to confront the myth of January 6th and the rise of Christian nationalism

While Mr. Dreyfus began serving a life sentence in harsh conditions at the notorious Devil’s Island prison off the coast of South America, his family in Paris began a campaign to prove his innocence. At first, they didn’t have anyone interested in the case. However, more and more people joined Dreyfus’s movement as evidence of a misguided justice gradually came to light, including the identity of the actual traitor, a dissolute nobleman named Ferdinand Varsin-Esterházy. Intellectuals began signing petitions and holding demonstrations in support of the Jewish officers.

Their big break came in January 1898, when popular novelist Emile Zola wrote,J’Accuse” [I Accuse]It exposed how the military captured an innocent man. Zola’s ploy inspired Dreyfus’s supporters, but it also enraged his opponents. in more than 69 towns and cities in France and colonial Algeria.Jacuse” Zola was tried for libel and was exiled from France.

For the next two years, French society was divided in two over the Dreyfus scandal. Those who fought on Dreyfus’ behalf believed that the incident was a test of the mottos of liberty, equality, and fraternity enshrined by the French Revolution. For anti-Dreyfus factions, many of whom continued to oppose his justice even after his innocence became clear, the military’s reputation was more important than abstract ideals. Many of them were also anti-Semites, believing that Jews like Dreyfus had no place in France, much less in France’s most sacred institution, the army.

This battle raised fundamental questions about French society. Can individual citizens claim the right to impartial justice even when that right conflicts with military or national interests? At a deeper level, the incident questioned whether religious and racial minorities even belonged in this country.

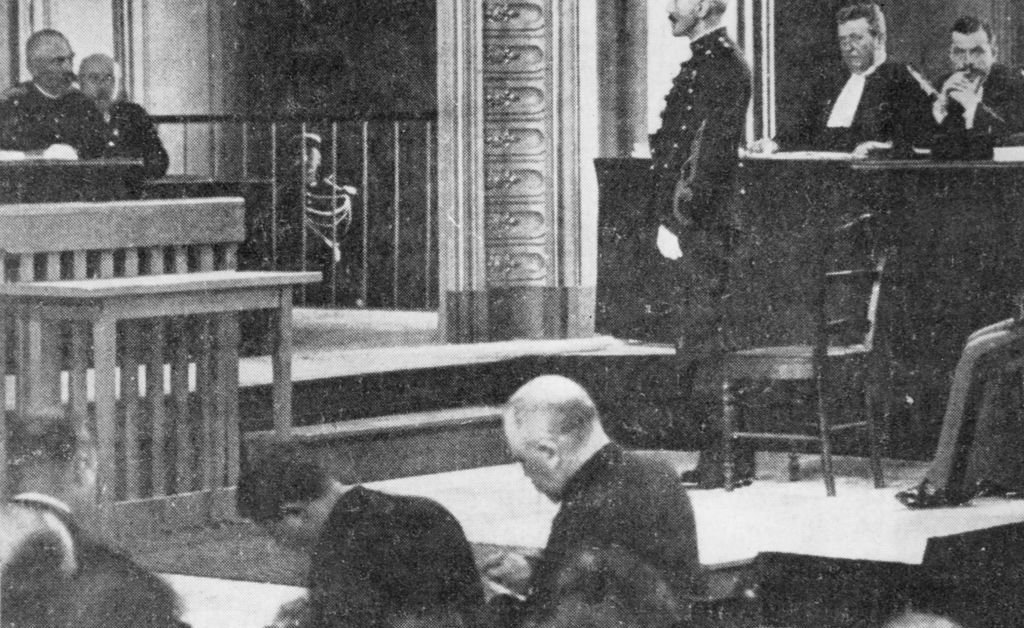

After much of the evidence secretly shown to Dreyfus’ judges was found to have been falsified, Dreyfus was brought back to France for a second court martial. In the late summer of 1899, journalists from all over the world gathered in Rennes, where the trial lasted several weeks. Soldiers patrolled the streets on foot and on horseback to maintain order. When the jury found Dreyfus guilty a second time, France appeared to be on the brink of civil war.

Instead, Prime Minister Pierre Waldeck Rousseau deftly pulled his country back from the brink. Given the opportunity to form a government by the newly installed President Émile Roubaix, Waldeck-Rousseau initially planned to select ministers only from among his fellow moderates, an action that was approved by the National Assembly. He knew it would happen. Instead, he reversed his course and floated the idea of bringing together ministers of vastly different political orientations, allied by two things: a belief in Dreyfus’ innocence and a desire to save the Republic. surfaced.

Among them was Alexandre Millerin, leader of the parliamentary socialists, who had long resisted making common cause with supporters of the bourgeois republic. He also brought in General Gaston de Galiffe, responsible for the Revolutionary Communard massacre of 1871 and one of the left’s most despised politicians. The Prime Minister’s bet was that each would bring in enough supporters to give the “Government of Defense of the Republic” a chance.

The backlash against those seeking to join the cabinet was predictable. A group of socialists disowned Milleran and formed their own party. The nationalist right similarly wasted no time in denouncing what they called the “Dreyfus service.”

However, the government survived to put an end to the incident. Waldeck-Rousseau used his power to pursue anti-Dreyfus strongholds that he saw as the greatest threat to the Republic, including the military and the Catholic Church. The Dreyfus incident itself remained a major problem. In the short term, Waldeck-Rousseau offered Dreyfus a pardon, which Dreyfus accepted on the condition that he continue to fight to restore his honor. Garife ordered his troops not to oppose the amnesty.

read more: What Washington can learn from its mayor

However, the solution proposed by Waldeck-Rousseau was not completely unilateral. He also passed an amnesty in December 1900. The pro-Dreyfus forces largely acquiesced, even though the military conspirators who had captured Dreyfus would be spared punishment. Waldeck-Rousseau was able to forge a compromise because political leaders put aside their differences for the greater good and encouraged their citizens to do the same.

However, although Waldeck-Rousseau succeeded in calming French politics in the short term, he was unable to truly eliminate the root causes of the conflict. The root of the divisions in French society stemmed from conflicts between left and right over the role of minorities in society and the importance of democratic institutions. These conflicts will smolder for decades. During World War II, the pro-Nazi National Revolutionary Government of Vichy saw itself as corrective to the victory of the Dreyfusard coalition. In many ways, the conflict between left and right that emerged during the incident continues to divide France to this day. During the last presidential election, far-right candidate Eric Zemmour said that Dreyfus’s innocence was “not clear”, an obvious dog whistle for his hard-line supporters.

This mixed verdict—calm in the short term but protracted by the problem—suggests that options exist to resolve, or at least de-escalate, the kinds of conflicts the United States finds itself in.I’m studying Grand denouement Looking at this incident, the centrist coalition believes that leaders must act decisively and bring those who have broken the law and sought to subvert democracy to their knees with strict measures and promises to curb their threat. In other words, it seems possible to govern effectively while ignoring fringe groups. of pardon. This would be much more difficult in America’s two-party system than in France’s parliamentary system, but compromise between opposing factions, as evidenced by Congress’s recent approval of aid to both Israel and Ukraine is not impossible.

But this incident, not just the current controversy at the time, is a warning to Americans that political hatred can be very persistent unless leaders address the root causes. The Dreyfus affair continues to outrage some in France, as the tensions it brought to the surface have not been fully resolved. This makes it clear that convincing citizens of the value of greater inclusiveness and the enduring value of democratic institutions is crucial. Only then can American society truly heal.

Maurice Samuels is a professor of French at Yale University and also directs the Yale Program for the Study of Antisemitism. His latest book is Alfred Dreyfus: The man at the center of the case. Published by Yale University Press in 2024.

Made by History is an article written and edited by expert historians that guides readers beyond the headlines. Learn more about Made by History at TIME..Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.