A version of this article appeared in CNN’s What Matters newsletter.Sign up for free to receive it in your inbox here.

CNN

—

When speaking to reporters outside a New York courtroom where he is on trial for falsifying business records, former President Donald Trump complains that he always wants to be with his voters.

“They’re trying to keep me out of the campaign,” he said Tuesday, suggesting the trial was part of an unsubstantiated conspiracy to tamper with the election.

It was a similar story last week when President Trump said he should campaign in battleground states.

“We’re in a courthouse right now, not in one of the 10 states I’d like to be in,” he told television cameras broadcasting his remarks across the country.

Meanwhile, President Joe Biden has scheduled visits to Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Florida. Trump chose not to campaign during Wednesday’s court session, but is scheduled to appear in New Jersey this weekend.

Both major candidates clearly value campaigning, the act of campaigning and speaking directly to voters.

It’s hard to believe that early American presidents never did any personal campaigning. They considered it beneath them and their status.

I spoke to Brendan Doherty, a political science professor at the U.S. Naval Academy and author of The Rise of the President’s Permanent Campaign and The Chief Fundraising Officer: Presidents and the Politics of Campaign Finance, We asked them about their plans for raising funds. The president lost his way and how this became a permanent campaign.

Our conversation, which took place via email, is below.

wolf: Why didn’t early presidents personally campaign?

doherty: In the early decades of the republic, presidential candidates adhered to the norm that they should not actively campaign. It was considered unseemly to seek office for which they had hoped to be elected. But that didn’t prevent them from finding other ways to communicate with voters.

wolf: How did early presidents who didn’t campaign get the message? Outside?

Doherty: Early presidential candidates did not actively campaign, but their supporters disseminated information on their behalf.

Newspapers in the early republic were openly partisan, with many of their articles openly praising or criticizing various candidates. In the 1800s, candidates did not attend political conventions, but supporters advocated for their preferred candidates in ways that promoted news coverage.

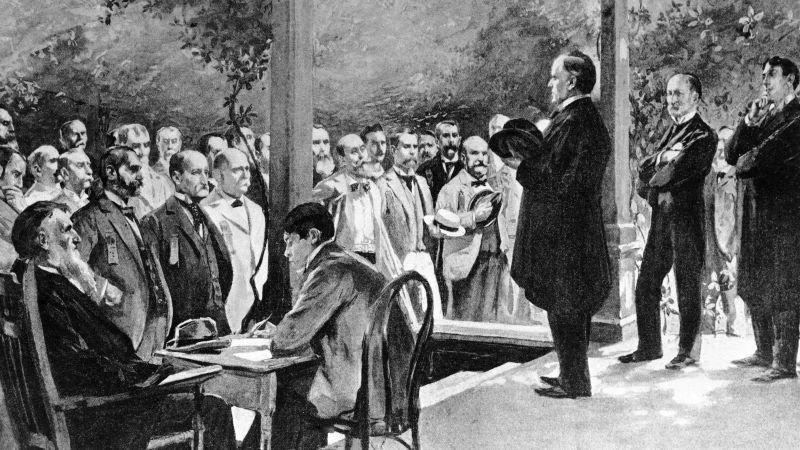

In the late 1800s, some presidential candidates launched what were called “front porch campaigns.” They addressed supporters in or near their homes, and newspapers covered these speeches and spread their messages across the country.

wolf: What are the key moments in the rise of the current campaign model?

Doherty: In 1866, President Andrew Johnson broke with precedent and campaigned aggressively in the midterm elections. His trip to deliver a series of speeches was dubbed “Swing Around the Circle,” and he was criticized for both his aggressive campaigning and his use of inflammatory rhetoric in doing so. It was done.

Two years later, the House of Representatives impeached Mr. Johnson for, among other things, giving a campaign speech that brought “disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt, and reproach” on Congress.

In 1896, Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan campaigned aggressively across the country, while the eventual winner, Republican William McKinley, campaigned on doorsteps.

In 1932, Franklin Roosevelt attended a party convention in person and became the first presidential candidate to accept an in-person nomination.

And in 1948, Harry Truman aggressively campaigned across the country, giving speeches from the back of a train in what became known as the No-Whistle Movement.

George Scadding/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

President Harry S. Truman speaks during the 1948 whistleblower campaign.

wolf: In your opinion, who is the most natural campaigner to run for president? What did they do differently?

Doherty: It’s hard to pick a single greatest campaigner, but two that come to mind are John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan.

Kennedy campaigned actively in the 1960 primary, but at the time, leading candidates often refrained from active campaigning during the nomination contest. However, he proved his electability to party leaders skeptical of a Catholic winning the White House, as the only major Catholic candidate lost to Herbert Hoover in a landslide in 1928. I wanted to.

Kennedy was widely seen as charming and eloquent on the stump, and his wins in the Wisconsin and West Virginia primaries helped him win his party’s nomination and the White House.

Reagan effectively used his years of acting and sense of humor in his presidential campaign. His voice, timing, and way of telling stories and jokes that connected with his audience earned him many accolades.

When the questioner implied that being an actor was not sufficient preparation for being president, President Reagan replied that he did not know how someone who was not an actor could be an effective president.

Ronald Reagan Library/Archive Photos/Getty Images

President Ronald Reagan waves to a line of people from the back of a limousine as he heads to his campaign destination in Fairfield, Connecticut, on October 26, 1984.

wolf: In a country of more than 335 million people, is an aggressive campaign that involves holding rallies and flying from destination to destination effective? There are only so many handshakes a candidate can shake. Moreover, most people already lean toward one political party or the other. What do you get when you put a candidate on the trail?

Doherty: Presidential candidates address only a relatively small portion of the American population, but more importantly, their campaigns reach a relatively small portion of the population of the small number of Electoral College battleground states that decide presidential elections. It can boost news coverage, and the effect is multifold. They are effective when it comes to getting their message across.

Political science research shows that local news coverage is often more advantageous to presidents and presidential candidates than national news coverage, so candidates often rely on local media to amplify their campaign messages. is conducting election activities as

Given the increasingly fragmented media environment, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for candidates to capture and maintain public attention, but that hasn’t stopped presidential candidates from trying.

wolf: I think the opposite of candidates not campaigning is the current system where candidates only temporarily suspend campaigning in order to govern. Why are permanent campaigns a problem and how can they be solved?

Doherty: Modern presidents campaign for themselves and their fellow party members throughout their terms. They raise campaign funds and visit key election states.

Presidents used to try not to appear overly focused on campaigning early in their terms, but that is no longer the case.

In the summer of his third year in office, Ronald Reagan refused to tell interviewers whether he would run for office. That’s because he said he doesn’t want every act of his presidency to be seen through a political lens.

In contrast, Donald Trump filed paperwork to form a reelection campaign committee on the day he took office in 2017, and held his first reelection campaign less than six months later, in June, his first year in office.

When a president begins an explicit campaign early in his term, he is responding to incentives in the electoral system. But time is a president’s most scarce resource, and time spent campaigning is time not spent fulfilling the important tasks for which he and someday she were elected.

For better or worse, there is no immediately obvious practical solution that would prevent a reelection-focused president from campaigning for reelection throughout his term.

wolf: If transportation and technology allow candidates to directly reach more people, where do you think campaign methods will go next?

Doherty: Advances in technology have allowed candidates to connect with the American public, from radio to television to the internet and now social media.

These developments, and advances in campaigns’ ability to reach voters in key states with messages that appeal to the issues they care about, have shifted campaigns away from broadcasting appeals and toward reaching potentially persuasive voters. We have started to carry out more focused efforts.

In an era when much of what voters do online can be tracked and used to build profiles of voters’ interests and preferences, this microtargeting is becoming increasingly precise, with campaigns increasingly tailored to specific messages. I am hopeful that it will be possible. The voters they are trying to reach.